The Association between Cholesterol and Mortality

Wenjie Sun., Center for Rural Health, Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences

Objective: To investigate the association between total cholesterol and mortality and examine whether the association varied by health status in elderly Chinese population.

Methods: The multivariable Cox regression was used to examine the adjusted total cholesterol with all-cause mortality by health status in a population-based cohort study. Confounders including age, sex, education, ever drinking alcohol, ever smoking, monthly personal expenditure, housing, and body mass index (BMI)

Results: Cholesterol was significantly positively associated with the CHD mortality (HR= 1.12, 95%CI 1.04-1.21) but negatively associated with all-cause (HR=0.91 95%CI 0.89-0.94) and non-CVD mortality, such as cancer and respiratory disease mortality. The association of total cholesterol with all-cause mortality varied by baseline health status (5 categories) (P=0.01). Higher cholesterol is associated with significantly decreased all-cause mortality in unhealthy but not healthy people.

Conclusions: The cholesterol-death association was positive for coronary heart disease but not other cardiovascular diseases, and inverse for cancer, respiratory diseases in both sexes. It appeared to benefit mainly older people in poor health. The harmful effect of cholesterol on mortality may have been overestimated in elderly people because of reverse causality. Lower TC might not an independent risk factor for increased mortality, but a mark in Chinese older people

Keywords: Cholesterol; elderly; mortality; reverse causality

Introduction

Total Cholesterol (TC) associated with mortality was well reported[1], although the relationship is not causal and could be explained by confounding such as chronic diseases et al [2] [3]. However, the relationship was modified by age[4], smoking[5], health status[6], and race[7]. For example, the lower TC predicted higher mortality in the oldest [8] and the J or U shape of association (mortality is non-linear and raise at both low or high TC level) also has been observed[9]. Moreover, low TC could be the indicator of poor health which contribute to non-cardiovascular mortality[10]. It also has been suggested that the observed negative association of TC and mortality in older people could be due to poorer health status amongst the inactive, i.e. reverse causality.

Moreover, the association between Total cholesterol (TC) and mortality differs in both magnitude and direction across specific causes of death,11 and may also vary by race and sex, [12, 13], i.e. there was positive correlation between TC and CHD mortality [14, 15], but an inverse association between TC and all-cancer mortality[16, 17]. For example the studies form the Eastern showed that the relationship was reversed, especially on the mortality from CHD and stroke [11, 18] [19] .

Most Asian studies from Japan, which have a high cut-off point of the TC in all-cause mortality than western population, shows an increase in the all-cause mortality in line.[20]

To the best of our knowledge, there was no community-base cohort study to clarify the association between TC and mortality in older Chinese. We examined the association, considering the modification effect of sex, age, smoking, and health status as well as multiple potential confounding factors in long follow-up times. We hypothesized that (a) TC was associated with all-cause and cause-specific mortality; and (b) these associations would be similar by sex, age, smoking, and health status.

Methods

Elderly Health Centers were established to deliver a health maintenance programmer at low cost (fees are waived for those with economic hardship) for the elderly, including health assessment, counseling, curative services and health education. All Hong Kong residents aged 65 years or older were encouraged to enroll. More women enrolled than men; otherwise the participants were similar in age, socio-economic status, current smoking and hospital use to the general elderly population.[21]

Trained nurses and doctors provided health assessments using standardized structured interviews and comprehensive clinical examinations. The health assessment covered functional status, falls, weight loss, use of medication, reported chronic illness (hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and /or asthma, heart disease, and stroke), lifestyle habits (physical activity, smoking history, and use of alcohol) and socioeconomic position (education, housing, and monthly expenditure). The participants were tested on: (1) functional ability on the Activity of Daily Living (ADL) and the five item Instrumental Activity of Daily Living (IADL); and (2) cognitive ability based on the Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT)-Modified.

Health status index

An 11-item morbidity index was created by counting chronic conditions (5 items), use of health services (2 items) and frailty (3 items). Chronic conditions included heart disease, stroke, diabetes, COPD/asthma and hypertension (reported or measured blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg). Measures of health service used were regular use of medication and any hospital admission in the last year. Measures of frailty were cognitive impairment (AMT <8), functional impairment (ADL/IADL >12) and two or more falls in the last 6 months. We also included unintentional weight loss >10 lb in the last 6 months. Health status was categorized using this morbidity index, as 0 (good or most healthy with no morbidity item), 1, 2, 3, and 4 or more items, with more items indicating unhealthier.

Baseline factors

The blood cholesterol level was category into the three levels:

1 A desirable level is less than 200 mg/dL (5.17 mmol/L)

2 Levels between 200 mg/dL and 239 mg/dL (5.17–6.18 mmol/L) are considered borderline for high cholesterol.

3 Levels at or above 240 mg/dL (6.21 mmol/L) are considered high cholesterol levels.

Follow-up and outcomes

Vital status was ascertained from death registration by record linkage using the unique identity card number. The last date of follow-up or censor date was December 31, 2005. Causes of death obtained were routinely coded according to the International Classification of Disease – 9th Revisions before 2001 and 10th Revision in and after 2001. Most Hong Kong residents die in the hospital, enabling accurate ascertainment of cause of death, which we have used previously in similar studies.[22] The primary outcome was all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality from major causes, i.e. respiratory disease (ICD-9 460-519 or ICD-10 J00-98), cancer (ICD-9 140-208 or ICD10 C00-D48), and cardiovascular disease (ICD-9 390-459 or ICD-10 I00-99).

Statistical analysis

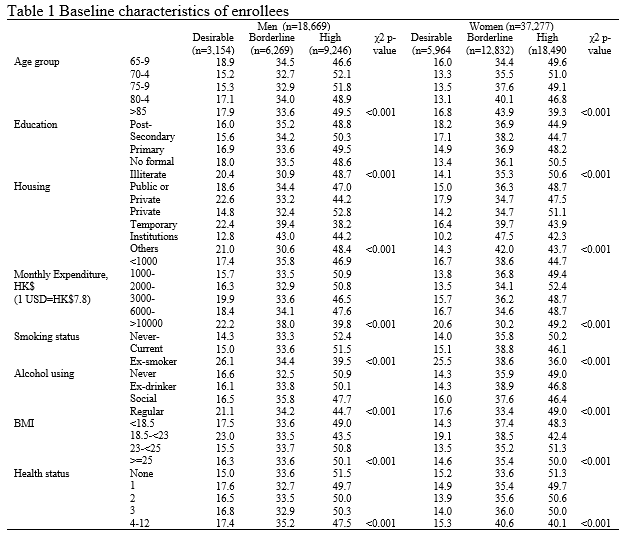

Chi-square tests were used to compare proportions of participant’s characteristics by physical activity category. The Cox proportional hazard model was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all-cause and cause specific mortality adjusted for baseline potential confounders. Confounders including age, sex, education, ever drinking alcohol, smoking, monthly personal expenditure, housing, and body mass index (BMI), as shown in Table 1. The proportional hazards assumption was checked by visual inspection of plots of log (- log (S)) against time, where S was the estimated survival function. Men and women were analyzed together unless there was evidence that physical activity had different effects by sex. Possible effect modification was assessed from the significance of the interaction terms and the heterogeneity of the effect across the strata. Participants who died of any other causes were regarded as censored at the date of death.[23, 24].

Results

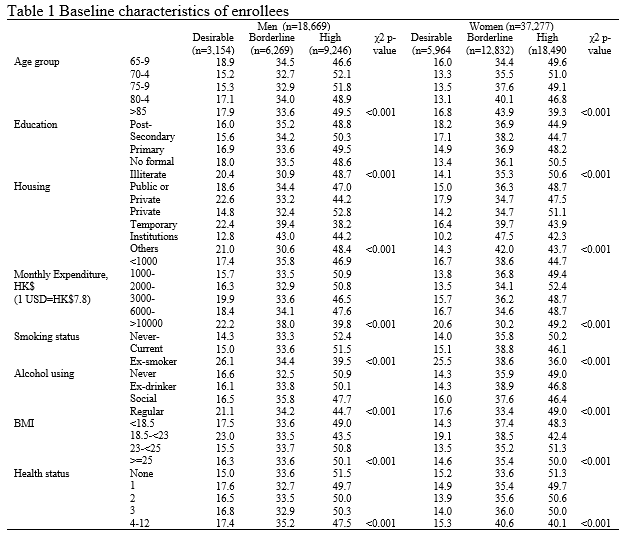

Of 56,088 participants, 142 were excluded because of missing information on potential confounders, and 55,946 (18,669 men and 37,277 women) were included in this analysis, including 6,295 deaths. There were 333,672 person years of follow up with an average of 6.0 years. Table 1 shows demographics, lifestyle, and health status at baseline by cholesterol level in both sexes. 5,439 (49.5%) men and 18,490 (49.6%) women had high cholesterol level. High cholesterol people were in the younger age groups, had higher expenditure, were less educated, and were ex-smokers, drinkers, sedentary, of normal weight or in poor health.

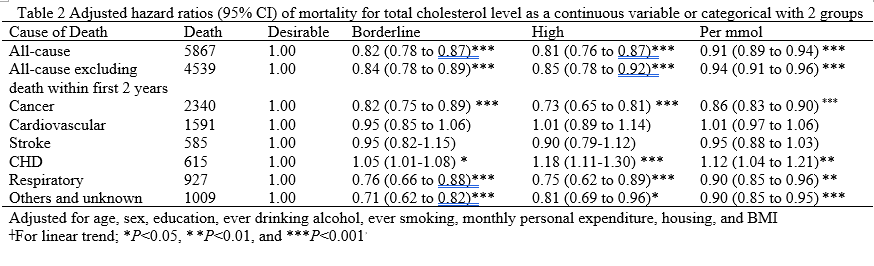

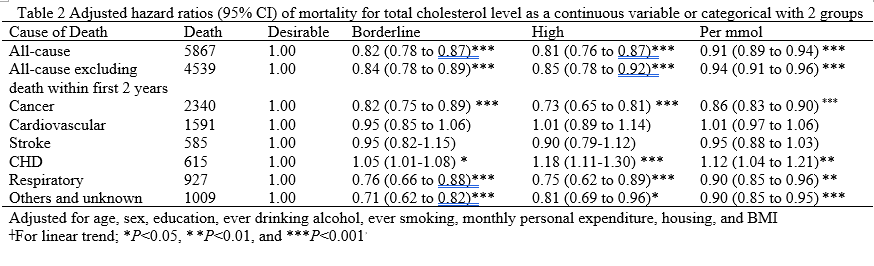

There was no evidence that cholesterol had different associations with mortality by sex (p value for interaction > 0.05). Table 2 shows that compared with desirable cholesterol level, borderline and high cholesterol level was associated with lower all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality i.e. cancer, respiratory disease mortality. After adjusting for risk factors, the HR per mmol cholesterol of all-cause mortality was 0.91 (95%CI 0.89-0.94). Similarly, high cholesterol was associated with lower mortality from respiratory,cancer, and CHD mortality with a clear dose response relationship, but not with lower mortality from cardiovascular and stroke mortality.

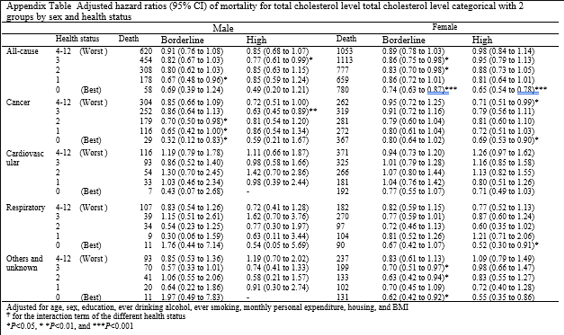

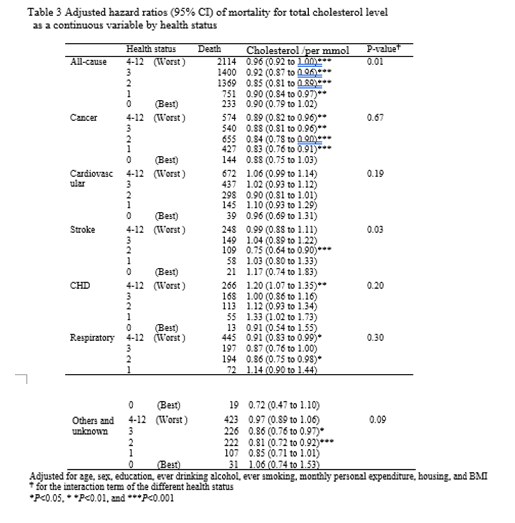

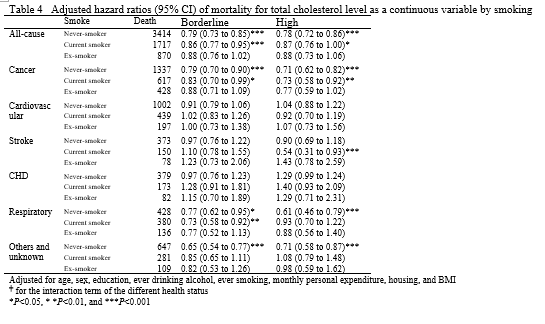

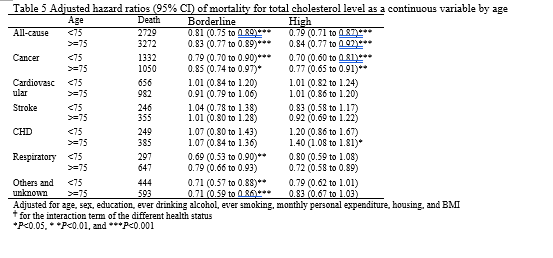

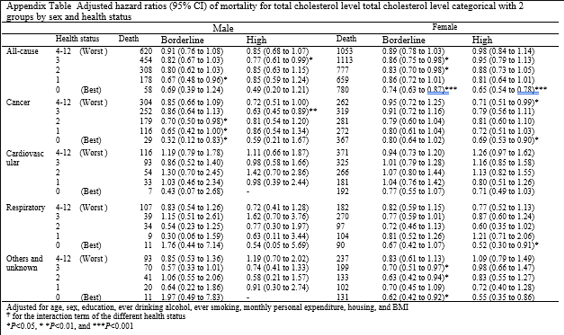

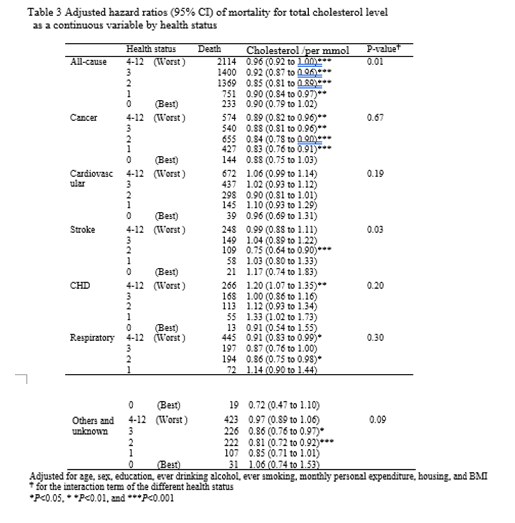

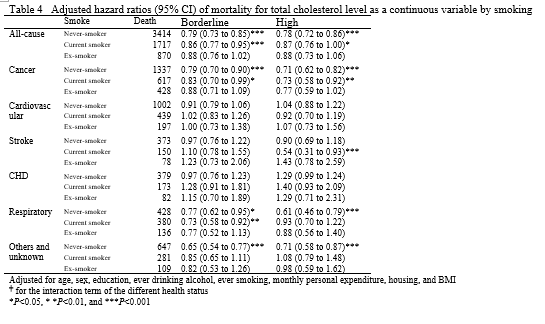

Table 3 shows the association of total cholesterol with all-cause mortality varied health status (p-value for interaction 0.01). Total cholesterol had no clear association with all-cause and cancer mortality in health group (health status=0), but associated with the lower all-cause and cancer mortality in the unhealthy groups.. It should be noted that cholesterol level was positively associated with CHD mortality in the unhealthy groups, but negative associated with stroke mortality. Compared with the inactive, in the healthiest group, desirable cholesterol (less than 5.17mmol) was not associated with mortality; however in the unhealthiest group, borderline and high cholesterol (more than 6.21 mmol) was associated with lower all-cause (hazard ratio 0.71; 95% confidence interval: 0.64-0.80), cardiovascular (0.81; 0.66-0.99), respiratory (0.56; 0.43-0.71), and other-cause (0.51; 0.40-0.66) mortality. Table 4 shows the cholesterol associated with lower all-cause and cause-specific mortality only in the non-smoke, but not Ex-smoker.

Discussion

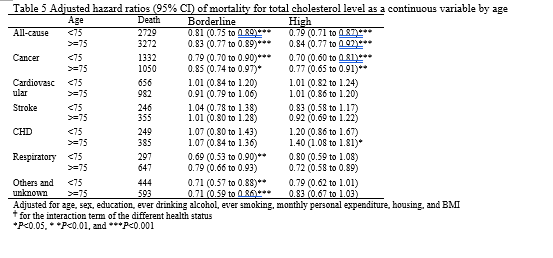

Lower TC was associated with increased mortality from all-cause and non-CVD mortality but decreased mortality from CHD. The relationship between TC and mortality in Chinese elderly did not vary by sex, age, and smoking but by health status.

Our results found that the lower cholesterol level associated with increased all-cause mortality were consisted with previous studies[25-27], but not all. Framingham study found that the relationship between TC and all-cause mortality was varied with age, it was positive (i.e., higher cholesterol level associated with higher mortality) at age 40 years, negative at age 80 years, and negligible at ages 50 to 70 years[4]. Casiglia et al pointed out that the relationship between TC and mortality in the elderly was J- shape [28], which might be easy explained by different effect components of TC, i.e. (HDL, LDL, VLDL) [29]. However, their study has a small sample size (3257 participants) and is based on primary care center which could have selection bias. The low TC levels and high mortality can be partially explained by confounding with other determinants of death and by preexisting disease at baseline, and TC-mortality associations are not homogeneous in the population.TC level was not associated with increased cancer or all-cause mortality in the absence of smoking, high alcohol consumption, and hypertension.[30] Apparently, this relationship may be modified by the health status. It should be noted that Hozawa et al found that low TC even can protect the cardiovascular disease mortality in the smoker[5].

As for CVD mortality, our results are in line with previous studies that no association between TC and CVD, but CHD mortality [3] [25, 28, 31, 32]. For example, the Seven Country Study found that cholesterol had effect on CHD mortality after take measurement error into account[33]. However, Cui et al found that lower TC levels were associated with higher mortality from CHD in Japanese [34]. Thus, it might be due to the national difference between the relationship of TC and mortality. Horenstein RB et al. showed that TC is more strongly associated with mortality in black women than in white women[7]. Another possible explanation is the reverse causality. Iribarren et al. pointed out that CVD diseases cause TC to decrease[35]. Ives et al. also found that very low cholesterol level in older individuals, more likely, is a marker of disease.[3] The associations between TC and CHD mortality might be non-causal, own to confounding. The relationship could be confounded by common cardiovascular risk factors[36], such as higher blood pressure level[1]. However, Amarenco et al found that the cholesterol level is a strong risk factor for CHD irrespective of age and blood pressure[37]. Moreover, Kjekshus et al insisted that the most robust predictive indicator of CHD is the TC [38].

As for non-CVD mortality, such as cancer, our results confirmed the inverse association of TC and cancer mortality [39] [40]. It should be noted that lower TC also significantly increased deaths not related to illness (such as deaths from accidents, suicide, or violence) [41, 42]. Thus, the protective effect is hard to explain by biological mechanism. One possible explanation is the survival bias due to the people with lower TC had a smaller possibility of death from CHD, which is one of the leading death causes compared to others reasons. Corresponding, those people have a bigger possibility to die from other non-CHD diseases including non-illness related reasons.

Limitations

Our study had some limitations. Firstly, those who came to the health center were healthier which could result in some volunteer bias. However, the EHC participants were similar to the general elderly population in several characteristics [21], but they might not be similar for others, such as self-rated health. Secondly, our average follow-up of 6.0 years was shorter than similar studies. It may underestimate the hazard ratio. Thirdly, we do not have the HDL or LDL which were more accurate. Fourthly, blood pressure which might be the potentiality confounding was not independently adjusted, although we included it in the morbidity index. The previous found blood pressure and TC were independent risk factors. Finally, our study was performed in a homogeneous population. Further prospective studies, especially those focusing on the elderly from different populations with repeated measurements on depression and medications, are warranted.

Conclusions

Our study found that the cholesterol-death association was positive for coronary heart disease but not other cardiovascular diseases, and inverse for cancer and respiratory diseases in both sexes. It appeared to benefit mainly older people in poor health. The harmful effect of cholesterol on mortality may have been overestimated in elderly people because of reverse causality. Lower TC might not be an independent risk factor for increased mortality, but a mark in Chinese older people. Further studies with longer follow-up are guaranteed.

Reference:

1. Lewington, S., et al., Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths. Lancet, 2007. 370(9602): p. 1829-39.

2. Clarke, R., et al., Cholesterol fractions and apolipoproteins as risk factors for heart disease mortality in older men. Arch Intern Med, 2007. 167(13): p. 1373-8.

3. Ives, D.G., et al., Morbidity and mortality in rural community-dwelling elderly with low total serum cholesterol. J Gerontol, 1993. 48(3): p. M103-7.

4. Kronmal, R.A., et al., Total serum cholesterol levels and mortality risk as a function of age. A report based on the Framingham data. Arch Intern Med, 1993. 153(9): p. 1065-73.

5. Hozawa, A., et al., Is weak association between cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease mortality observed in Japan explained by low total cholesterol? NIPPON DATA80. Int J Epidemiol, 2007. 36(5): p. 1060-7.

6. Liu, J., et al., Predictive value for the Chinese population of the Framingham CHD risk assessment tool compared with the Chinese Multi-Provincial Cohort Study. JAMA, 2004. 291(21): p. 2591-9.

7. Horenstein, R.B., D.E. Smith, and L. Mosca, Cholesterol predicts stroke mortality in the Women's Pooling Project. Stroke, 2002. 33(7): p. 1863-8.

8. Spada, R.S., et al., Low total cholesterol predicts mortality in the nondemented oldest old. Arch Gerontol Geriatr, 2007. 44 Suppl 1: p. 381-4.

9. Tuikkala, P., et al., Serum total cholesterol levels and all-cause mortality in a home-dwelling elderly population: a six-year follow-up. Scand J Prim Health Care, 2010. 28(2): p. 121-7.

10. Wannamethee, G., et al., Low serum total cholesterol concentrations and mortality in middle aged British men. BMJ, 1995. 311(7002): p. 409-13.

11. Choi, J.S., Y.M. Song, and J. Sung, Serum total cholesterol and mortality in middle-aged Korean women. Atherosclerosis, 2007. 192(2): p. 445-7.

12. Cai, J., et al., Total cholesterol and mortality in China, Poland, Russia, and the US. Ann Epidemiol, 2004. 14(6): p. 399-408.

13. White, A.D., C.G. Hames, and H.A. Tyroler, Serum cholesterol and 20-year mortality in black and white men and women aged 65 and older in the Evans County Heart Study. Ann Epidemiol, 1992. 2(1-2): p. 85-91.

14. Keil, J.E., et al., Serum cholesterol--risk factor for coronary disease mortality in younger and older blacks and whites. The Charleston Heart Study, 1960-1988. Ann Epidemiol, 1992. 2(1-2): p. 93-9.

15. Holme, I. and S. Tonstad, Association of coronary heart disease mortality with risk factors according to length of follow-up and serum cholesterol level in men: the Oslo Study cohort. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil, 2011.

16. Schuit, A.J., et al., Inverse association between serum total cholesterol and cancer mortality in Dutch civil servants. Am J Epidemiol, 1993. 137(9): p. 966-76.

17. Song, Y.M., J. Sung, and J.S. Kim, Which cholesterol level is related to the lowest mortality in a population with low mean cholesterol level: a 6.4-year follow-up study of 482,472 Korean men. Am J Epidemiol, 2000. 151(8): p. 739-47.

18. Nago, N., et al., Low Cholesterol is Associated With Mortality From Stroke, Heart Disease, and Cancer: The Jichi Medical School Cohort Study. J Epidemiol, 2011. 21(1): p. 67-74.

19. Tsuji, H., Low serum cholesterol level and increased ischemic stroke mortality. Arch Intern Med, 2011. 171(12): p. 1121-3.

20. Okamura, T., et al., The relationship between serum total cholesterol and all-cause or cause-specific mortality in a 17.3-year study of a Japanese cohort. Atherosclerosis, 2007. 190(1): p. 216-23.

21. Schooling, C.M., et al., Obesity, physical activity, and mortality in a prospective chinese elderly cohort. Arch Intern Med, 2006. 166(14): p. 1498-504.

22. Lam, T.H., et al., Mortality and smoking in Hong Kong: case-control study of all adult deaths in 1998. BMJ, 2001. 323(7309): p. 361.

23. Satagopan, J.M., et al., A note on competing risks in survival data analysis. Br J Cancer, 2004. 91(7): p. 1229-35.

24. Andersen, P.K., S.Z. Abildstrom, and S. Rosthoj, Competing risks as a multi-state model. Stat Methods Med Res, 2002. 11(2): p. 203-15.

25. Woodward, M., et al., Elevated total cholesterol: its prevalence and population attributable fraction for mortality from coronary heart disease and ischaemic stroke in the Asia-Pacific region. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil, 2008. 15(4): p. 397-401.

26. Onder, G., et al., Serum cholesterol levels and in-hospital mortality in the elderly. Am J Med, 2003. 115(4): p. 265-71.

27. Strandberg, T.E., et al., Low cholesterol, mortality, and quality of life in old age during a 39-year follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2004. 44(5): p. 1002-8.

28. Casiglia, E., et al., Total cholesterol and mortality in the elderly. J Intern Med, 2003. 254(4): p. 353-62.

29. Law, M. and N. Wald, Cholesterol, statins, and mortality. Lancet, 2008. 371(9619): p. 1161-2; author reply 1162-3.

30. Iribarren, C., et al., Serum total cholesterol and mortality. Confounding factors and risk modification in Japanese-American men. JAMA, 1995. 273(24): p. 1926-32.

31. Houterman, S., et al., Total but not high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is consistently associated with coronary heart disease mortality in elderly men in Finland, Italy, and The Netherlands. Epidemiology, 2000. 11(3): p. 327-32.

32. Thomas, F., et al., Combined effects of systolic blood pressure and serum cholesterol on cardiovascular mortality in young (<55 years) men and women. Eur Heart J, 2002. 23(7): p. 528-35.

33. Boshuizen, H.C., et al., Effects of past and recent blood pressure and cholesterol level on coronary heart disease and stroke mortality, accounting for measurement error. Am J Epidemiol, 2007. 165(4): p. 398-409.

34. Cui, R., et al., Serum total cholesterol levels and risk of mortality from stroke and coronary heart disease in Japanese: the JACC study. Atherosclerosis, 2007. 194(2): p. 415-20.

35. Iribarren, C., et al., Low serum cholesterol and mortality. Which is the cause and which is the effect? Circulation, 1995. 92(9): p. 2396-403.

36. Hu, P., et al., Does inflammation or undernutrition explain the low cholesterol-mortality association in high-functioning older persons? MacArthur studies of successful aging. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2003. 51(1): p. 80-4.

37. Amarenco, P. and P.G. Steg, The paradox of cholesterol and stroke. Lancet, 2007. 370(9602): p. 1803-4.

38. Kjekshus, J., What are the effects of patient age and blood pressure on the cholesterol-related risk of vascular mortality? Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med, 2008. 5(6): p. 310-1.

39. Iso, H., et al., Serum total cholesterol and mortality in a Japanese population. J Clin Epidemiol, 1994. 47(9): p. 961-9.

40. Nago, N., et al., Low Cholesterol is Associated With Mortality From Stroke, Heart Disease, and Cancer: The Jichi Medical School Cohort Study. J Epidemiol, 2010.

41. Muldoon, M.F., S.B. Manuck, and K.A. Matthews, Lowering cholesterol concentrations and mortality: a quantitative review of primary prevention trials. BMJ, 1990. 301(6747): p. 309-14.

42. Lindberg, G., et al., Low serum cholesterol concentration and short term mortality from injuries in men and women. BMJ, 1992. 305(6848): p. 277-9.

Appendix Table