Policy Implementation Framework: Addressing Prescription Drug Costs Through Government Price Negotiation

KRUPA PATEL, DHA, MBEMH, MHA, MGH, Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences (OSU-CHS) OSU School of Health Care Administration

BINH PHUNG, DO, MHA, MPH, Oklahoma State University Department of Pediatrics

Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences (OSU-CHS)

OSU School of Health Care Administration

Executive Summary

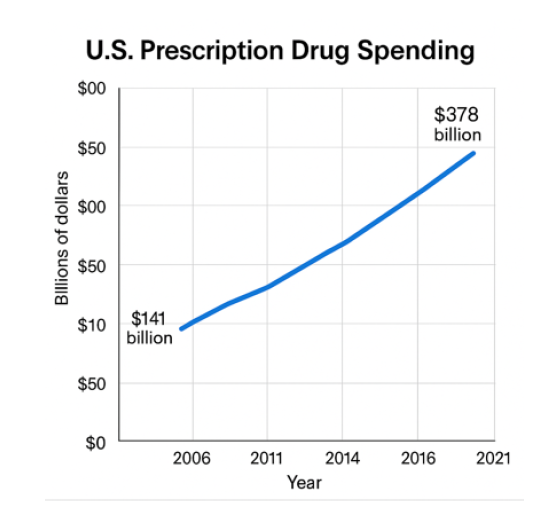

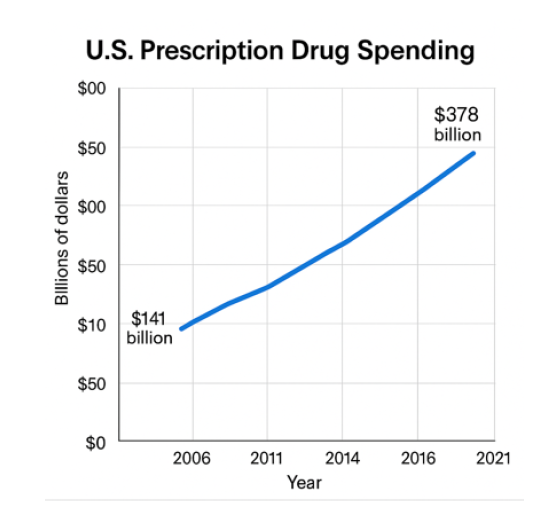

Most Americans spend more on prescription drugs than any other country worldwide. Americans spend roughly $100 billion annually on drugs.1 The cost of prescription drugs impacts access to healthcare and adherence to treatment, especially for vulnerable groups like the elderly and those with low incomes.4 Although both sides of the aisle agree it’s a problem, they can’t necessarily agree on a policy. This suggests that the government should negotiate the prices of prescription drugs to reduce their costs through multi-phased approaches. The proposal presents plans to address stakeholder concerns and enhance affordability and sustainability.

Introduction

The United States is a high-income country that spends more per capita on prescription drugs than any other country. Studies show that Americans spend around $100 billion annually on prescriptions.1

Almost 25% of Americans do not take their prescribed medicines as directed because they cannot afford them. 3 This means around a quarter of Americans are unable to afford them. Healthcare costs will keep rising, and disparities will keep multiplying.

For decades now, prescription drug costs have been an ongoing issue in the American healthcare system.3 Increased prices have drawn scrutiny from policymakers, advocacy organizations, and healthcare providers. As new specialty drugs continue to enter the market, which are often the most expensive, the issue has become more pressing. According to recent estimates, the average price of a brand-name drug exceeds $6,000 per year (or about $500 per month), which is quite high.3 Additionally, evidence shows that nearly one in five adults under age 65 did not fill a prescription because of cost.3

Both parties are aware of the problem of affordable pharmaceuticals. Despite bipartisan recognition of this problem, there is still no agreement on the best policy to reduce costs or continue funding for new investigational drugs. Measures are being taken, which include the $35 price cap on insulin for Medicare beneficiaries by the Inflation Reduction Act, but more needs to be done to ensure a sustainable and fair solution to rising drug costs.4

The next section will examine the policy proposal in terms of its content, process, actors, and context, using the policy triangle model.

Content

The goal of the policy is for the government to negotiate prescription drug prices to lower healthcare costs and improve access to drugs. The literature supports this policy objective, as access to affordable prescription drugs will enhance adherence, thereby improving health outcomes. The purpose of this policy brief is to build on the stakeholder analysis and policy issue framing assignments to substantiate the need.

The proposed plan would allow Medicare to negotiate prices directly with drug manufacturers, particularly for high-priced drugs like insulin, cancer medications, and other drugs used in chronic disease treatment. 4 Over time, more drugs will be added for price negotiation to improve affordability.

Specific Objectives

• Ensure lower prices for costly prescription drugs used by people on Medicare.

• Help poor and vulnerable people receive life-saving medicines.

• Establish a structure for ongoing negotiation and price changes with the market.

• Encourage rivalry between manufacturers to decrease costs through innovative approaches.

Literature shows that government negotiation can yield significant savings. For instance, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), which negotiates drug prices, obtains much lower prices than Medicare for the same drugs. If Medicare negotiates drug prices just as the VHA does, it will maximize its purchasing power and pay less, particularly for high-cost specialty drugs.

High prescription drug prices have a profound impact on the healthcare system by increasing overall healthcare costs, reducing patient adherence to treatment, and imposing a financial burden on Medicare and vulnerable populations. Research shows that when drug prices are unaffordable, patients are less likely to adhere to their prescribed treatment plans, which can result in worsened health conditions, increased hospitalizations, and higher healthcare expenditures. By allowing Medicare to negotiate prices directly with pharmaceutical manufacturers, the proposed policy aims to address these systemic issues. Implementing this policy would require amending the Social Security Act to grant Medicare the authority to negotiate prices and establishing new regulatory guidelines to standardize the negotiation process. Evidence-based literature strongly supports the potential benefits of this approach. For example, a study by the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that the VHA, which negotiates drug prices, paid an average of 54% less per unit for a sample of 399 prescription drugs compared to Medicare Part D.6 Additionally, 233 of those drugs were at least 50% cheaper in the VHA system than in Medicare.6 If Medicare were to adopt a similar negotiation approach, it could realize substantial savings, enhance accessibility to essential medications, and improve overall health outcomes for diverse populations.

Process

The suggested policy will start by amending the Social Security Act to allow Medicare to negotiate directly with pharmaceutical firms. Implementing this strategy would involve broad rulemaking and engagement with key federal entities.

• The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will establish standards for negotiating and ensuring compliance with negotiated prices.

• The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) partnership will determine how discussions about drug costs would affect the investigation and approval of drugs.

• The government health department will coordinate efforts for diversity in healthcare and expand health business opportunities.

Evaluation Metrics

• Reduction in average prescription drug prices for Medicare beneficiaries. 4

• Improved accessibility and adherence to essential medications.

• Stakeholder satisfaction and compliance with negotiated prices.

• Regular monitoring of health outcomes related to improved drug access.

Policy Implementation Science

• Utilize frameworks like the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to ensure consistent and effective implementation.

• Monitor short-term and long-term outcomes to assess the effectiveness and make necessary adjustments.

• Encourage continuous feedback from stakeholders to refine implementation strategies.

In addition to the CMS and the FDA, other agencies under the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS), such as the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), may also play roles in the policy's implementation or oversight. While CMS and FDA are the primary agencies involved in drug pricing negotiations and approval processes, HRSA and AHRQ could contribute to evaluating health outcomes and ensuring equitable access for underserved populations. Additionally, SAMHSA and CDC may provide valuable data and recommendations regarding medications related to mental health and chronic disease management. As part of the policy modification phase, continuous monitoring and evaluation will be conducted to assess the policy's effectiveness. This will involve analyzing price reductions, adherence improvements, stakeholder satisfaction, and overall health outcomes. Adjustments will be made as necessary based on these evaluations. Furthermore, trade-offs between affordability, innovation, and access will be carefully considered during the negotiation process to ensure that the policy achieves a balance that benefits all stakeholders.

Actors

The stakeholders involved in this policy proposal include:

1. Medicare negotiation of affordable prescription drug prices is advocated by the Government & Policymakers (Group A). A most potent force for political action in the USA has arguably been the role of interest groups. Interest groups are coalitions of people who seek either to benefit from government action or to prevent what they perceive as damaging government action.

2. The pharmaceutical industry opposes price controls due to the reduction in profits and impact on innovation. 5 According to the industry, high drug prices are essential to fund research and development.

3. Patients and advocacy organizations support price controls to increase accessibility to important drugs. High drug prices have the biggest impact on patients, especially those with chronic conditions or financial limitations.

4. Healthcare providers and insurers (Group D): Cost and adherence reduction calls for support; they will offer different views depending on their financial interests. Insurers want to cut healthcare spending by negotiating medication costs/prices.

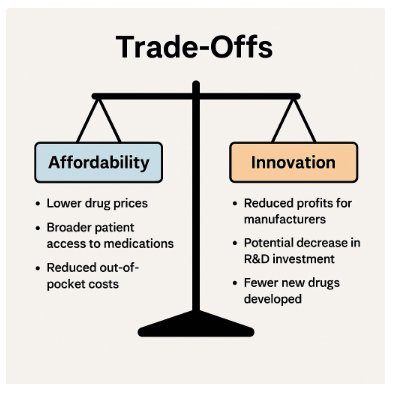

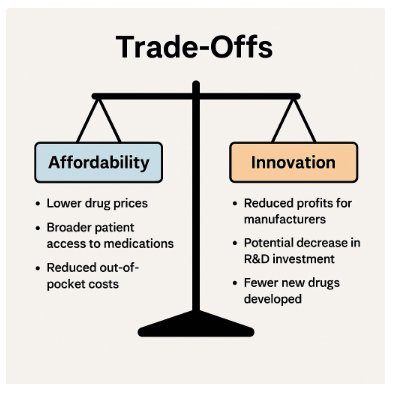

Trade-offs

Making sure the proposal can be a success requires ensuring that the interests and views of relevant parties don’t conflict. To gain the backing of many stakeholders, there will need to be a careful balancing of affordability, innovation, and accessibility.

1. Affordability vs. Innovation

A cut to profits caused by government-negotiated drug prices could lead to less research. Policymakers have to balance the immediate benefits of lowering costs with the future need for innovation. 2, 5

Pharmaceutical companies are particularly concerned that price negotiations will prevent the recovery of research and development (R&D) costs.

Strategies to Balance Interests

• Incentives:

o Companies that comply with the negotiated pricing will be given tax breaks.

o Funds for developing medicines for unique ailments or neglected groups.

o Collaborating with organizations to help fund research.

• Penalties:

o Tax non-complying companies on high-profit margins.

o Limitations on market access for firms unwilling to negotiate prices.

o Increased oversight to prevent prices gouging.

2. Targeting Specific Demographics or Drug Categories

Focusing on high-cost, life-saving medications like insulin or cancer drugs offers the best opportunity for impact, potentially at the expense of other medications. The approach should begin by focusing on the most expensive drugs, in a phased manner.

Strategies to Balance Interests

• Negotiations gradually include a wider range of drugs.

• A subsidization scheme for drugs excluded from negotiation could benefit consumers and the industry alike.

• Encouraging manufacturers to offer essential drug discounts.

3. Cost of Short-term vs. Long-term.

Price capping may not provide immediate relief to consumers, but it could result in lower competition or fewer generics in the future. 2, 5

Strategies to Balance Interests

• Regularly reviewing negotiated prices to match market conditions.

• Offering incentives to generic drug makers to enter the market.

• Supporting research efforts to create low-cost alternatives to costly medicines.

4. Convincing Pharmaceutical Companies to Participate.

To foster participation, a mixture of rewards and deterrents must be employed.

Incentives

• Grants for drug development of rare disease products.

• Reduced corporate tax rates for compliant companies.

• Fast-track approvals for companies that comply.

Penalties

• No approval for companies that are non-cooperative.

• Stricter inspections and regulations for companies that do not comply with the law.

• Imposing fines on excessive profit margins.

The combination of rewards and penalties will also make negotiation easier, as it will require both coordination and compliance. Policymakers must ensure that options related to affordability and innovation are effectively balanced.

Along with stakeholders such as the government, policymakers, pharmaceutical companies, patients, patient advocacy organizations, health care providers, and insurers, it may also be important to assess power dynamics and potential partnerships among these groups. Pharmaceutical companies possess significant financial resources, research capabilities, and lobbying power, which they may use to push back against negotiating lower prices by arguing that high prices are necessary to fund research and innovation. In contrast, patient groups and advocacy organizations hold intangible power, such as public goodwill and advocacy support, using compelling stories, statistical evidence, and public opinion to campaign for lower drug prices.

Policymakers have the authority to permit or prohibit drug price negotiations. Additionally, they can conduct public awareness campaigns, establish stakeholder feedback loops, engage in bipartisan negotiations, and promote transparent communication to enhance stakeholder engagement and discussion of implementation.

Above all, negotiations among stakeholders can help enhance the acceptability of the policy. For instance, patient advocacy organizations and policymakers could collaborate to signal urgency in reducing drug prices, while pharmaceutical companies could partner with research institutes to convey their commitment to innovation with adjusted profit margins.

Moreover, stakeholders may present evidence-based arguments to support their reasoning; for example, pharmaceutical companies may provide evidence of research and development costs to justify pricing, while advocacy groups may present statistical data and testimonials to illustrate how high drug prices create barriers.

To achieve a more balanced policy outcome, carefully crafted incentives and penalties addressing the varying interests and power dynamics in this case would be essential.

Context

Political Climate

The current political climate is deeply divided into health policy. Democrats generally favor government intervention to lower costs, while Republicans often emphasize market-driven solutions. Building bipartisan support will require compromises, such as including incentives for innovation while ensuring affordability. This divide makes policymaking challenging but also presents opportunities for collaboration when mutual benefits are identified.

Strategies to gain bipartisan support may include:

• Highlighting the economic benefits of reduced drug prices, such as improved workforce productivity and decreased healthcare costs.

• Framing the policy as a market-enhancing approach that encourages competition and innovation.

• Emphasizing the need for compromise and collaboration to achieve meaningful reform.

Inclusivity

While inclusivity was previously mentioned, this section will be expanded to detail how the policy will prioritize the voices and experiences of marginalized groups throughout the implementation process.

• The policy must ensure that marginalized groups' voices are heard, particularly those most affected by high drug prices, such as low-income individuals, racial minorities, and rural populations.

• Implementing targeted outreach and consultation mechanisms can help ensure inclusivity in the policymaking process.

• Policymakers should actively seek input from advocacy groups representing vulnerable populations during negotiations and implementation.

• Establishing feedback mechanisms will allow marginalized groups to express concerns and suggest improvements throughout the process.

Different social determinants of health (SDOH) and non-medical factors contribute to the implementation of this policy. They include economic inequality, cultural beliefs, education, housing instability, and systemic racism. The high prices of prescription drugs disproportionately affect marginalized groups such as low-income individuals, racial minorities, rural populations, and other communities who face barriers to access due to inadequate insurance coverage, lack of healthcare access, and financial instability.

Due to these structural inequities, poor health outcomes and worsening chronic conditions occur because of restricted access to vital medicines. Policies aimed at dismantling structural racism and promoting health equity are essential. Making essential medicines affordable and accessible for all would reduce health inequalities, increase adherence levels, and improve health outcomes.

The policy must be designed inclusively, prioritizing and integrating the lived experiences of relevant stakeholders from marginalized groups into the policymaking process. To gather responses from those most affected by high drug prices, mechanisms such as targeted outreach should be implemented.

Additionally, the policy must function not only as a mechanism but also as a lever to enhance health equity through improved access and affordability of medicines for disadvantaged groups. Demonstrating how the policy will improve health outcomes for a wide variety of people, particularly those suffering from chronic conditions, individuals of low socioeconomic status, or those facing geographical barriers, will be important.

Furthermore, showcasing how lowering drug prices can contribute economically through improved productivity and reduced healthcare spending will be essential. Ultimately, implementing this policy in a way that addresses systemic inequities and political divides will be necessary.

Conclusion

Achieving equitable access to affordable prescription drugs will require bipartisan support, smart policy, and prioritization of public health over industry profits. Medicare negotiation at the beginning, followed by expansive price reductions for high-cost drugs, may provide a viable path forward through a phased approach. If there are more manufacturers and stronger policies supporting generics, there will be less inflation and lower prices.

The policy brief demonstrated that it is possible for Medicare to engage in price negotiation. It cites models like the Veterans Health Administration where negotiations resulted in substantial cost reductions. By following this path, the U.S. can make significant progress toward reducing inequity in access while keeping essential medications affordable for Americans.

It will be important to monitor the policy's impacts going forward and adjust the approach to address any unintended consequences if necessary. For reform to be sustainable and meaningful, there must be a commitment to transparency, inclusivity, and ongoing collaboration.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Dr. Binh Phung for valuable guidance and insightful review throughout this research process.

Appendices

Appendix 1A – Policy Formulation Steps

1. Introduce legislative bill for Medicare price negotiation authority.

2. Conduct stakeholder consultations and public commentary.

3. CMS and FDA establish regulatory guidelines for negotiation.

Appendix 1B – Federal Agencies Involved

• Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)

• Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

• Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)

• Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)

Appendix 1C – Stakeholder Analysis

• Supporters: Patient advocacy groups, healthcare providers, bipartisan policymakers

• Opposers: Pharmaceutical industry, due to concerns about profit impacts and potential reduced innovation.

References

1. Zobeck, T. (2014). How Much Do Americans Really Spend on Drugs Each Year? The White House. Retrieved from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2014/03/07/how-much-do-americans-really-spend-drugs-each-year.

2. Blume-Kohout, M. E., & Sood, N. (2013). Market Size and Innovation: Effects of Medicare Part D on Pharmaceutical R&D. Journal of Public Economics, 97, 327–336.

3. Kesselheim, A. S., Avorn, J., & Sarpatwari, A. (2016). The High Cost of Prescription Drugs in the United States: Origins and Prospects for Reform. JAMA, 316(8), 858–871.

4. Sayed, M., Finegold, K., Olsen, T. A., Ashok, K., Schutz, S., Sheingold, S., De Lew, N., & Sommers, B. D. (2023). Inflation Reduction Act Research Series: Medicare Part D Enrollee Out-of-Pocket Spending: Recent Trends and Projected Impacts of the Inflation Reduction Act. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

5. Maynard, A., & Bloor, K. (2015). Regulation of the Pharmaceutical Industry: Promoting Health or Protecting Wealth? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 108(6), 220–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076814568299

6. U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2021). Department of Veterans Affairs Paid About Half as Much as Medicare Part D for Selected Drugs in 2017. U.S. Government Accountability Office. Retrieved from https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-111