When Fatty Liver Isn’t the Full Story: Recurrent Hypoglycemia

Leading to Insulinoma Diagnosis: A Case Report

Bene’ Valentine, Kyrsten, D.O.

Department of Internal Medicine, Oklahoma State University, Tulsa, OK

Wilson, Andrew, D.O.

Department of Internal Medicine, Oklahoma State University, Tulsa, OK

Magana Herrera, Fernando D.O.

Department of Gastroenterology, Oklahoma State University, Tulsa, OK

Corresponding Author:

Fernando Magana Herrera, D.O.

Email: fernando.magana@okstate.edu

Address: 744 West 9th Street, Tulsa, Oklahoma 74127-9028

Conflicts of Interest: None to report

Financial disclosure/funding: None to report

Abstract

Our case is a 33-year-old Hispanic male who was referred to our gastroenterology clinic for evaluation of elevated transaminases and hepatic steatosis. He did have a social history of alcohol use which is a common cause of hepatic steatosis, however our patient had also been having recurrent episodes of hypoglycemia, syncope, and weight gain.1 His symptoms well described Whipple’s triad, a diagnostic hallmark for true hypoglycemia.2 Once imaging and workup had been performed, an insulinoma, an insulin secreting neuroendocrine tumor, was found at the pancreatic tail. Once further imaging and biochemical testing had confirmed the diagnosis, curative surgery was performed. Postoperatively, he had complete resolution of hypoglycemia and significant weight loss. The following case illustrates the diagnostic challenges and multidisciplinary approach involved in identifying and managing insulinoma in a patient initially referred for evaluation of elevated transaminases.

Key words: Insulinoma, Whipple’s Triad, Hepatic Steatosis, Case Report

Introduction

Insulinomas are rare, typically benign, neuroendocrine tumors originating from pancreatic islet β-cells.3 Patients often present with neuroglycopenic symptoms such as tremors, diaphoresis, confusion, visual disturbances, headaches, or even coma in severe cases.4 The presence of these symptoms, plasma glucose <55 mg/dL, and symptom resolution after glucose administration constitutes Whipple’s triad—a key diagnostic criterion for true hypoglycemia.2 Biochemical confirmation of insulinoma involves inappropriately elevated insulin (≥3 µU/mL) during hypoglycemia, with elevated C-peptide (≥0.6 ng/mL) and proinsulin (≥5 pmol/L). When Whipple’s triad is not clearly demonstrated, a supervised 72-hour fast remains the gold standard for diagnosis.3

Once the biochemical diagnosis of insulinoma is established, tumor localization is typically pursued using non-invasive imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Contrast-enhanced CT is the most commonly employed technique, with a reported sensitivity of approximately 70–80%.3 In patients with a high clinical suspicion for insulinoma but negative non-invasive imaging, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) offers superior localization, with a sensitivity of up to approximately 93%, outperforming CT in many cases.5

Surgical resection remains the definitive and often curative treatment for localized insulinomas. Laparoscopic enucleation is typically the preferred approach with more extensive pancreatic resections reserved for tumors that are poorly localized or situated near critical structures such as the pancreatic duct or major vessels.6 Histopathologic analysis may include immunohistochemical staining for markers such as chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and insulin.3 In addition, a Ki-67 proliferation index and mitotic rate should be obtained to establish a tumor grade.7

Case Report

A 33-year-old Hispanic male presented to the gastroenterology clinic for evaluation of elevated transaminases. He had a past medical history of reactive airway disease, sleep apnea, hypertension, pulmonary nodule, gastroesophageal reflux disease, hepatic steatosis and obesity. He endorsed alcohol use every 2 weeks with 15-18 beers consumed. He began drinking alcohol around age 20. He has two tattoos from a tattoo parlor 14 years prior. He notes his mother had fatty liver disease and his father may have had a liver dysfunction. There is no documented family history of cirrhosis. His aunt on his father's side had an unknown malignancy and he had not undergone any previous colon cancer screening at time of evaluation. He reported he had recent weight gain and difficulty with low blood sugars, leading his primary care physician (PCP) to consider a potential insulinoma and endocrinology referral. At the time of initial gastroenterology consultation, he was pending a continuous glucose monitor approval and had an upcoming appointment with endocrinology.

On physical examination, he was obese and in no acute distress. Head/eyes/ear/nose/throat examination was without abnormality. He had a regular cardiac rate and pulses without murmur and normal pulmonary effort without respiratory distress. Abdomen was flat with no distension or mass noted, and bowel sounds normal with no abdominal tenderness. There was no evidence of skin tags, jaundice, or rash and there were no focal neurological deficits. One month prior to consultation, significant labs are noted in Table 1. CT abdomen pelvis with and without contrast four months prior to consultation revealed pancreas and adrenal glands unremarkable with mild cystitis, hepatic steatosis, small pulmonary nodule of the left lower lobe per report.

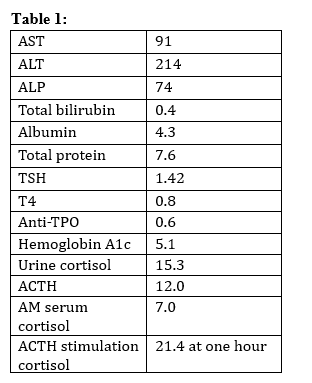

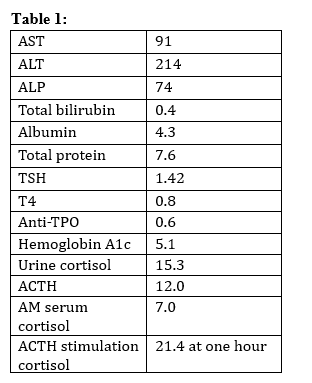

Table 1. Lab values noted one month prior to gastroenterology consultation.

AST = aspartate aminotransferase, ALT = alanine transaminase, ALP = alkaline phosphatase, TSH = Thyroid stimulating hormone, Anti-TPO = Antithyroid peroxidase antibodies, ACTH = adrenocorticotropic hormone

Patient’s clinical history was discussed and there was consideration for Whipple’s triad as he had endorsed recent episodes of syncope with symptoms of hypoglycemia, necessitating he eats to feel better. The patient was encouraged to set up an overnight sleep study, a combination of hypocaloric diet and moderate-intensity exercise, and nutritionist evaluation for weight loss. Complete alcohol cessation was recommended and an acute hepatitis panel and hepatitis b core total antibodies were ordered alongside a liver ultrasound with elastography, repeat liver chemistries, and prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR) to evaluate liver synthetic function. F-Actin, anti-nuclear antibody, ceruloplasmin, ferritin, and total iron binding capacity (TIBC) with iron level were ordered. Hepatitis viral serologies were negative, autoimmune labs were negative, and the iron studies yielded no evidence of increased iron stores. Repeat hepatic labs showed total bilirubin 0.5, aspartate aminotransferase (AST): 108, alanine transaminase (ALT): 228, alkaline phosphatase (ALP): 65, albumin: 4.4, total protein:7.5, and ceruloplasmin:21. Liver ultrasound showed hepatic steatosis and hepatomegaly. No suspicious liver lesion found on ultrasound. The median shear wave elastography measurement is 5.84 kPa: F0-1 (normal or mild). Additional hypoglycemia studies were ordered with a random insulin level elevated at 241 with an elevated proinsulin level of 39.4 and C-Peptide of 12.8.

The patient was evaluated by endocrinology and noted a continued twenty-three-pound weight gain within a three-month clinic evaluation period. Endocrinology noted hypoglycemia and elevated transaminases likely due to alcohol use. Differential included an insulinoma with no obvious mass noted on ultrasound imaging or nesidioblastosis. Endocrinology repeated a random insulin level which was elevated at 156 with an elevated proinsulin level of 26.0 and C-Peptide of 10.9.

Gastroenterology followed for evaluation for insulinoma causing hypoglycemic episodes with syncope, weight gain, and hepatic steatosis. Chromogranin A level was ordered with plan for Dotatate PET scan pending results and STAT referral for EUS with biopsy was made. He noted that he had an overall weight gain of one-hundred pounds now in twelve months and had recent blood sugar levels as low as the 20s. He underwent extensive education of pancreas anatomy and neuroendocrine tumors and was advised to seek immediate emergency medical assistance if symptoms arise. Chromogranin A level was drawn and was 50ng/ml. Repeat CT abdomen pelvis multiphase with and without contrast revealed 4.3 cm pancreatic tail mass with homogenous hyperenhancement consistent with an insulinoma as reported in history and bilateral fat containing inguinal hernias. The hepatobiliary and surgical oncology department reviewed the case and recommended partial pancreatectomy with plan for enucleation, although formal distal pancreatectomy with possible splenectomy may be required. EUS was deferred. Splenectomy vaccines were administered and peri-operative 30-day mortality of 1% was quoted.

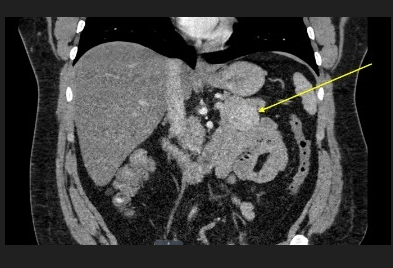

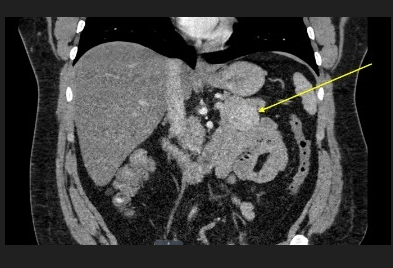

Figure 1: CT abdomen pelvis with and without contrast was ordered and revealed a 3.8x 4.0 cm solid enhancing mass arising from the pancreatic tail. There was no pancreatic ductal dilatation or atrophy. This may represent an insulinoma in the appropriate clinical setting.

The patient underwent robotic-assisted laparoscopic pancreatic enucleation (partial distal pancreatectomy, spleen-preserving) and was found to have an exophytic, hypervascular, well-encapsulated lesion originating from the inferior aspect of the pancreatic tail, closely excised with parenchymal-sparing enucleation approach. Repeat CT abdomen pelvis with contrast for left upper quadrant abdominal pain several days postoperatively showed postoperative changes of the tail in the pancreas, with non-visualization of the previously seen exophytic mass. There was a high-density fluid and air within the operative bed at the tail of the pancreas which was presumably postoperative in nature, acute pancreatitis could not be excluded. Fatty infiltration of the liver and a 12 mm soft tissue nodule in the right omentum was noted, also presumably due to postsurgical changes. Tissue pathology results revealed a 3.7x3.4x2.4 cm G1 well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor with mitotic rate: 1, Ki-67 labeling index: 3%. Immunohistochemical results were chromogranin A positive, synaptophysin positive.

Three months post operatively; the patient was seen and evaluated doing very well. He lost thirty-five pounds of body weight and had no further issues with hypoglycemia on his continuous glucose monitor. CT Abdomen pelvis multiphase with and without contrast revealed improved postoperative changes around the pancreatic tail without evidence of residual recurrent pancreatic mass. Previously described right omental nodule was smaller than on the previous exam. A 4 mm pulmonary nodule in the left lower lobe was indeterminate, but most likely benign and stable compared to previous. Six-months later, he was seen for post-surgical follow up, noted no further hypoglycemia, eating well with stable weight, and advised he did not need surveillance imaging.

Discussion

Insulinomas are the most common functioning endocrine neoplasm of the pancreas.5 Around 90% of insulinomas are nonmetastatic and are most commonly evenly distributed over the entire pancreas.5,7 Curative surgical excision remains the treatment of choice with the 5-year survival of patients with a nonmetastatic insulinoma reported to be 94% to 100%.7 However, because of the rare nature of insulinomas and variety of symptoms, diagnosis can be challenging. Keeping Whipple’s triad in mind can help lead to early diagnosis and intervention as noted in this case.

Along with the hypoglycemic events that characterize an insulinoma, another symptom that can be reported is weight gain.5,8 The weight gain and metabolic derangements seen in a patient with an insulinoma is typically due to multiple factors. Firstly, since the insulinoma is an insulin secreting tumor, this has an anabolic effect on the body.9 This means there is an increase in the breakdown of glucose to be transformed into glycogen and fat, the storage form of glucose. Secondly, patients recognize that their symptoms occur with episodes of hypoglycemia and will eat often to avoid this.8 Obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and alcohol use are all of our patients risk factors for hepatic steatosis, excessive lipid accumulation in hepatocytes.1,10 The incidental finding of elevated aminotransferases from hepatic steatosis was just one clinical feature that helped lead to the diagnosis of an insulinoma.

Although tumor enucleation is the treatment of choice for benign and solitary insulinomas, it may not always be feasible. For tumors that are deeper or have closer proximity to the pancreatic duct, a distal pancreatectomy or a pancreatoduodenectomy is performed.12,13 A distal pancreatic insulinoma that cannot undergo enucleation can have a distal pancreatectomy performed that is spleen preserving, however if the splenic vessels or hilum are involved, splenectomy is indicated.12,14 If splenectomy is a possibility, pneumococcal, meningococcal, and Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccines are indicated preoperatively.15 The American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends urgent control of dietary measures (carbohydrate-rich meals), somatostatin analogues, and antitumor therapies (peptide receptor radionuclide (PRRT) and targeted therapy with everolimus) in the setting of malignancy or if surgical is not immediately feasible.11

Localization and removal of an insulinoma is curative for most patients.13 Recommended surveillance of functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are CT of the abdomen or MRI every year for the first 3 years, and then every 1 to 2 years to not go beyond 10 years. At 10 years, the discussion of risk vs benefit should be held with the patient. It is important to note that patients with a Ki-67 index greater than 5% or patients with any positive lymph nodes are considered to be in the high-risk category and surveillance imaging is more frequent. Surveillance labs with random insulin, proinsulin levels, and c-peptide may be useful, however published data to support this is scarce.16 As this patient had a Ki-67 index of 3% without any identified positive lymph nodes, long term surveillance imaging was not necessary.

Conclusion

This case emphasizes the importance of maintaining a broad differential diagnosis when evaluating patients with elevated transaminases, hepatic steatosis, and rapid weight gain. Although insulinomas are rare, taking a full history to understand the entire clinical picture is crucial to initiate further workup in a timely manner. In this patient, what initially appeared to be primarily a liver-related problem ultimately helped lead to the discovery of an insulinoma. A multidisciplinary approach allowed for timely diagnosis, successful surgical management, and resolution of symptoms. This case demonstrates how a comprehensive evaluation on a common liver condition such as hepatic steatosis can significantly improve outcomes for patients with rare but curable conditions.

Acknowledgements:

Author contributions: All authors contributed equally to this manuscript. All identifying information has been removed from this case report to protect patient privacy.

References:

1. Idilman IS, Ozdeniz I, Karcaaltincaba M. Hepatic steatosis: Etiology, patterns, and quantification. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2016;37(6):501-510.

2. Desimone ME, Weinstock RS. Hypoglycemia. In: Endotext. MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

3. Zhuo F, Menon G, Anastasopoulou C. Insulinoma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

4. Meyerhardt JA, Kulke MH, Turner JR. Cancer of the gastrointestinal tract and neuroendocrine tumors. In: Atlas of Diagnostic Oncology. Elsevier; 2010:169-232.

5. Okabayashi T, Shima Y, Sumiyoshi T, et al. Diagnosis and management of insulinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(6):829-837.

6. Hoskovec D, Krška Z, Škrha J, Klobušický P, Dytrych P. Diagnosis and surgical management of insulinomas-A 23-year single-center experience. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(8):1423.

7. Hofland J, Refardt JC, Feelders RA, Christ E, de Herder WW. Approach to the patient: Insulinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024;109(4):1109-1118.

8. Rokutan M, Yabe D, Komoto I, et al. A case of insulinoma with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Roles of hyperphagia and hyperinsulinemia in pathogenesis of the disease. Endocr J. 2015;62(11):1025-1030.

9. Tokarz VL, MacDonald PE, Klip A. The cell biology of systemic insulin function. J Cell Biol. 2018;217(7):2273-2289.

10. Pouwels S, Sakran N, Graham Y, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a review of pathophysiology, clinical management and effects of weight loss. BMC Endocr Disord. 2022;22(1):63.

11. Kulke MH, Shah MH, Benson AB III, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors, version 1.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(1):78-108.

12. Shin JJ, Gorden P, Libutti SK. Insulinoma: pathophysiology, localization and management. Future Oncol. 2010;6(2):229-237.

13. Navez J, Marique L, Hubert C, et al. Distal pancreatectomy for pancreatic neoplasia: is splenectomy really necessary? A bicentric retrospective analysis of surgical specimens. HPB (Oxford). 2020;22(11):1583-1589.

14. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. General recommendations on immunization --- recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(2):1-64.

15. Perez K, Del Rivero J, Kennedy EB, et al. Symptom management for well-differentiated gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: ASCO guideline. JCO Oncol Pract. Published online May 9, 2025:OP2500133.

16. Singh S, Moody L, Chan DL, et al. Follow-up recommendations for completely resected gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(11):1597-1604.