Beyond Bans: Rethinking School Smartphone Policies

CHARYNE T. ZEINOUN, MS-HIM

Doctoral of Healthcare Administration (DHA) Candidate

Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences (OSU-CHS)

OSU School of Health Care Administration

BINH PHUNG, DO, MHA, MPH

Oklahoma State University Department of Pediatrics

Oklahoma State university Center for Health Sciences (OSU-CHS)

OSU School of Health Care Administration

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

FUNDING: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

CORRESPONDENCE: Charyne T. Zeinoun, email: charyne.t.zeinoun@okstate.edu

ABSTRACT

Problematic smartphone use (PSU) during school hours has been increasingly linked to academic disengagement, heightened social comparisons, and escalating mental health risks among adolescents. In response to these growing concerns, many school districts across the nation have adopted a variety of restrictive smartphone policies. However, most of these existing policies often target singular objectives—such as discipline, engagement, or safety–rather than embracing the broader potential of integrated, public-health interventions. This policy brief advocates for a multidimensional policy framework that reconciles cognitive, clinical, equity, and governance considerations. Specifically, we urge school districts to: (1) engage in stakeholder listening conduct a comprehensive landscape scan to identify system needs and constraints, encouraging co-design of smartphone policies with input from key stakeholders; (2) undertake drafting and vetting processes in which new policies are reviewed through legal, equity, and operational lens to ensure alignment with cognitive and clinical criteria before adoption; (3) adopt and implement new policies with structured rollouts that delineate clear restriction and exception pathways, safeguarding instructional time, supporting effective crisis communication, and accommodating individual learning needs; and (4) commit to ongoing evaluation and iterative adjustment, using predefined indicators to monitor impacts and refine policies continually. Unlike total bans that depend solely on enforcement, this adaptive and data-informed four-phase cycle reframes restrictive smartphone policies as dynamic, developmentally responsive, and aligned with public health interventions. Such reframing is intended to not only enhance the feasibility and legitimacy of these policies but also strengthen their relevance to youth mental health.

Keywords: Youth mental health, students, adolescents, access, smartphones, policies, problematic smartphone use (PSU), smartphone restriction

SCOPE OF THE ISSUE

The nation’s youth mental health emergency is sobering in scope, with alarming statistics: four in ten high school students report persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, 29% report poor mental health, more than 20% seriously consider suicide, and one in ten attempts it.1,2 Rising internalizing symptoms have coincided with the rapid escalation of smartphone and social media exposure,3 which has been linked to increased depressive symptoms and suicidality in youth.4,5 These statistics hint at a public health crisis with broad implications for educational attainment, social development, and long-term health. Mounting evidence implicates problematic smartphone use (PSU) as a central contributor: observational data confirm that smartphone engagement during instructional time is both frequent and sustained,3 and such pervasive digital engagement disrupts sleep, displaces physical activity, heightens exposure to cyberbullying, contributes to behavioral health disorders, and fosters harmful social comparisons—factors associated with anxiety, depression, and diminished academic performance.6-8 As a preventive measure, school-based policies on smartphone± access have gained widespread attention. Yet these policies are contested, reflecting deeper tensions at the nexus of technology, adolescence, and public education—including questions of developmental appropriateness, equity, and civil rights.

Refer to Appendix 1A – Policy Taxonomy and Definitions for a detailed taxonomy of smartphone policy models, terminologies, and educational time segments.

POLICY OBJECTIVES

Current policies on smartphone access during school hours aim to improve learning conditions and support students’ mental and emotional health but have demonstrated vulnerability to implementation failures such as unstable compliance enforcement, inequitable discipline patterns, and interference with protected accommodations.9-14 The intent of the proposed policy framework is to reinforce a regulatory posture that is preventive without being punitive and implementable without collapsing clinically and developmentally necessary exceptions. Key objectives include:

• Protect instructional time by restricting smartphone access during defined instructional school hours while avoiding overbroad prohibition in low-risk contexts.

------------------------------------

± The authors acknowledge that terminology around “smartphones”, “cell phones”, and “mobile devices” is in flux (e.g., cell phone—more common in North America; mobile phone or mobile—more common in the United Kingdom and internationally; smartphone; and the broader term mobile device, which also encompasses tablets and laptops, along with less common labels such as handset, wireless phone, and hand phone). Terms such as “mobile device,” “mobile users,” or “mobile phone users” are more inclusive than “cell phone,” yet most U.S. and global data continue to be collected and reported with traditional phone-centric terms. This policy brief uses a combination of device-specific and umbrella terminology interchangeably, such as “smartphones” and “cell phones” based on the available data used for reporting.

• Preserve crisis communication and necessary accommodations through structured exception pathways for behavioral-health needs, disability protections, and emergency communication, consistent with MTSS (Multi-Tiered Systems of Support) guidance that access to student well-being supports must be maintained even when regulatory controls are applied.15

• Reduce enforcement inequities and legal vulnerability by replacing teacher-level discretionary enforcement with explicit and repeatable rules.

• Reinvest “phone-free” time into intentional alternatives (e.g., connectedness-building practices and digital literacy integration) to address risk reduction and resilience, consistent with evidence that stronger school connectedness is associated with lower PSU and social media use among adolescents.16

DOMINANT STAKEHOLDER TENSIONS

The position of key stakeholder groups – including students, parents and guardians, educators, policymakers, and legal and advocacy organizations - on school-based smartphone policies converges around a set of recurring tensions. First, debates over autonomy and safety reflect two competing understandings of harm: while some stakeholders support cell phone restrictions as preventive measures to reduce distraction, cyber-risk, and mental overload, others emphasize the loss of access to crisis supports, behavioral-health tools, and parent-child contact as a distinct safety risk.17-25 Second, stakeholders diverge over whether policies should be uniform or locally adaptive. Advocates for standardization view consistency as essential to fairness and compliance, whereas others argue that rigid uniformity fails in divergent school environments and generates resistance or inequitable enforcement when contextual variation is ignored.12,20-26 Third, the tensions between restriction and mental-health access centers on whether policies reduce exposure to digital harms without obstructing protected accommodations or clinically relevant support pathways.17-19,22,27,28 These tensions clarify why blanket or total bans have encountered predictable failure modes and why conditional access policies (CAP) and hybrid-conditional restriction (HCR) approaches are more structurally compatible with real implementation constraints. Importantly, they also identify where stakeholder feedback must be incorporated upstream – not only during policy design but during iterative testing and refinement – such that real user experience, compliance behavior, and unintended effects can be fed back into adjustment cycles rather than treated as post-hoc resistance.

ANALYSIS OF REAL-WORLD MODELS

Real-world experience with school-based smartphone policies offers a clear pattern of what succeeds, what fails, and what design elements determine durability. New York City (NYC) provides one of the strongest success cases with its HCR policy prohibiting unsanctioned use “Bell-to-Bell” but delegates storage and handling plans to schools, supplies targeted funding for storage needs, requires a parent-contact pathway during the day, mandates consultation with teachers, parents, and students in developing local smartphone policies, and includes explicit protections against inequitable discipline.29 This alignment of structured restriction, local implementation flexibility, stakeholder inclusion, and equity safeguards maps closely to the same principles embedded in a framework that adopts characteristics of both the HCR and CAP models and helps explain the policy’s operational stability.

Conversely, two prominent case studies illustrate the fragility of prohibition-based designs. In California, Yondr-based total bans have suffered from circumvention, staff enforcement burden, theft and damage disputes, and equity disputes when exceptions are improvised rather than designed upstream.25 In Texas, schools that rely on discipline escalation rather than structural design have produced a discipline spiral, reinforced inequitable patterns in enforcement, and left the underlying drivers of PSU unaddressed.14 In both settings, the absence of exception logic and the reliance on punishment rather than system design produce predictable erosion.

Evidence from Florida’s statewide ban further reinforces the same pattern: policy outcomes hinge not on smartphone restriction alone but on the implementation architecture. Despite uniform prohibition of in-school [smartphone] access, districts exhibited wide variations in compliance, academic gains, and disciplinary spillovers depending on whether local plans included exception pathways, stakeholder buy-in, and substitutes for social or regulatory functions. Where bans were implemented as total bans (AKA “pure prohibition”), gains were limited or offset by enforcement conflict and inequity; where policy implementation incorporated structured design features, effects were more durable.30

Several jurisdictions now function as cautionary signals that design choices, not simply restrictiveness, determine success. Oklahoma’s Bell-to-Bell state mandate leaves exception criteria and implementation architecture to school districts, creating risk for policy drift, local contradiction, and stakeholder confusion when exceptions are not standardized.31 Georgia’s K-8 guidance attempts to preserve Individualized Education Program (IEP) /504 plan (ensures learning accommodations for students with disabilities) access and route emergency communications through school systems and does not require stakeholder co-design – conditions that may weaken legitimacy and fidelity even before implementation begins.32 These case examples illustrate that even well-intentioned policy restrictions can unravel when stakeholder consultation, exception pathways, and adaptation mechanisms are not embedded at the front end.

Altogether, these cases reinforce the core rationale for a multidimensional model. NYC’s success demonstrates that smartphone restriction can be durable when coupled with local design authority, equity safeguards, and protected access channels; California and Texas illustrate ban failure when they collapse accommodations and substitute structurally enforceable and inherently stable for reactive punishment of violations; Oklahoma and Georgia show that partial or vague structures lacking explicit exception logic or co-design requirements are vulnerable to fragmentation and stakeholder backlash. What distinguishes durable policy is not severity but architecture. These convergent lessons indicate that the question is no longer whether to restrict smartphones in school, but whether the restriction architecture preserves the developmental, clinical, and equity conditions that determine whether a policy stabilizes or collapses in practice.

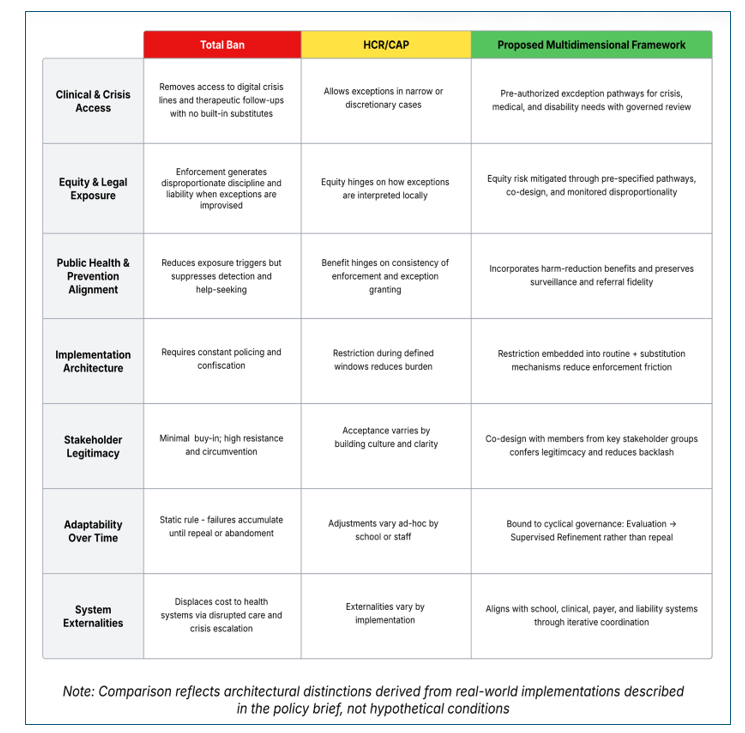

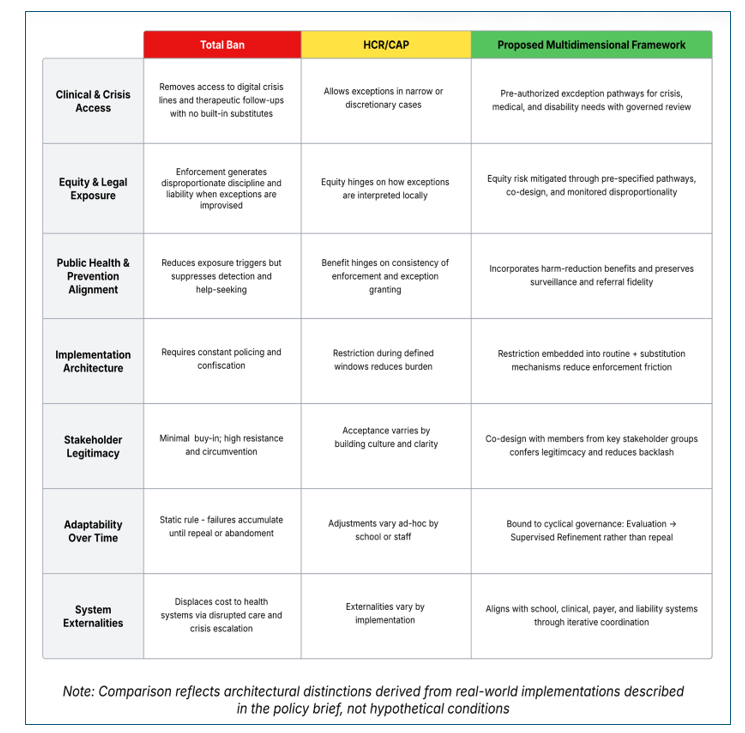

To clarify the design distinctions driving divergent outcomes across implementations, Figure 1 compares total bans, HCR/CAP approaches, and the proposed multidimensional framework.

Figure 1. Comparative Policy Architecture

PROPOSED MULTI-DIMENSIONAL POLICY FRAMEWORK

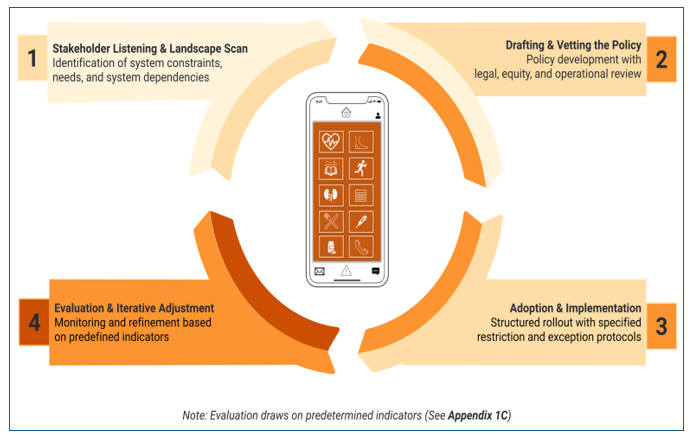

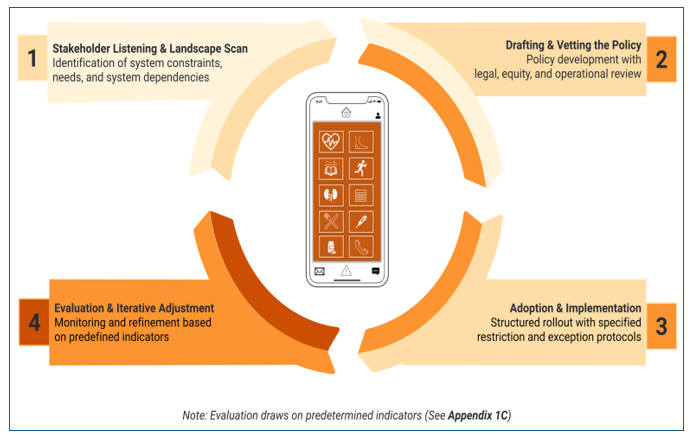

Total bans on smartphone have produced predictable failure patterns: enforcement strain, equity distortion, and erosion of protected access.9 To reconcile cognitive, clinical, equity, and governance considerations, this policy brief advocates for a multidimensional framework designed to ensure that exposure is appropriately regulated while preserving developmental and clinical safeguards. This framework is not a moderated version of total bans, but a structural alternative organized to ensure that smartphone policy is co-designed, context-fitted, revisable, and accountable over time. Evidence from, but not limited to, Florida’s statewide [smartphone] prohibition reinforces that real-world outcomes depend on policy design: even with uniform restriction, school districts exhibited divergent academic and disciplinary effects depending on whether implementation included exception protocols, stakeholder buy-in, and functional substitutes for removed behaviors.10,29-34,40 Accordingly, this framework embraces an iterative, four-phase cycle (Figure 2), emphasizing continuous development, adoption, evaluation/assessment, and refinement of smartphone policies.

1. Stakeholder Listening & Landscape Scan

Districts should begin by eliciting input from key stakeholders to identify the conditions under which smartphone restriction generates either benefit or harm. This phase should not be a preference poll but a diagnostic exercise to surface operational constraints, clinical access dependencies, equity risks, and foreseeable points of compliance friction. A concurrent review of the regulatory environment, collective bargaining considerations, and lessons from comparable implementations can prevent policy designs that are misaligned with local capacity or legal.9,34 Co-design at this stage strengthens downstream legitimacy and reduces the likelihood of resistance emerging as a response to exclusion from policy formation.

2. Drafting & Vetting the Policy

A draft policy may then be constructed that limits smartphone access during instructional time, preserves clearly defined exception pathways for crisis communication and documented medical or disability accommodations, embeds digital-literacy instruction, and redirects phone-free time toward structured practices that build connectedness. Rather than presuming completeness, the draft can then be subjected to structured vetting with stakeholder panels, legal and equity review, and operational stress-testing to identify failure modes in advance. This iterative vetting process functions as a safeguard against the common failure pattern of total bans, which collapses distinctions between ordinary use and protected need and rely on discipline to compensate for design omissions.

3. Adoption & Implementation

Once revised through vetting, the policy may be formally adopted with a building-level implementation plan that specifies when instructional-time restriction applies, how inaccessibility is achieved, what communication channels substitute for confiscated access, and how compliance is checked without continuous surveillance. Methods for rendering smartphones inaccessible may differ across schools but should be uniform within each building to avoid inequitable or improvised enforcement. Training and communication may be extended not only to staff but to students and families to ensure implementation fidelity is built through socialization rather than enforced solely through sanction. This phase translates the policy from a written directive into a stable routine architecture.

4. Evaluation & Iterative Adjustment

Following adoption, school districts may evaluate implementation using predefined indicators such as enforcement burden, distribution of disciplinary actions, exception requests and approvals, continuity of crisis access, compliance drift, and observed impacts on classroom disruption. Rather than treating friction or deviation as evidence of failure, findings from this phase can be utilized to refine procedures, clarify ambiguities, or redesign elements that produce inequitable or counterproductive effects. In contrast to total bans – which cannot evolve without repeal – this framework treats feedback as a governance input, enabling smartphone policy to remain aligned with cognitive, clinical, equity, and governance considerations over time (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Iterative Policy Design

ADAPTIVE GOVERNANCE

Under the proposed framework, policy governance is structured like an HCR model in which schools manage day-to-day implementation while school districts maintain authority over structural revisions. Schools can make minor procedural refinements that do not alter the scope or criteria of the restriction (e.g., adjusting storage routines, classroom-level compliance checks), whereas substantive changes to policy design, exception eligibility, or enforcement rules are subject to district-level review and approval to preserve consistency and legal defensibility. This division allows implementation to remain context-responsive without fragmenting the policy architecture across schools.

Governance operates through a scheduled review cycle in which districts receive structured implementation data from schools and determine whether revision is warranted. Schools are expected to report on predefined indicators rather than subjective impressions. Districts may use these data to authorize refinements when the policy produces unintended harm, operational instability, or equity distortion. Where the indicators show stable function with acceptable variance, the policy may be retained without modification while routine monitoring continues. This governance approach replaces the binary logic of “adopt or repeal” with a structured mechanism for supervised revision, ensuring that smartphone policy remains a managed intervention rather than a static rule that drifts, fractures, or reverts under pressure.

Refer to Appendix 1C – Tracked Indicators for a list of predefined indicators.

HEALTH SYSTEM COMPONENTS AFFECTED

Although based in educational settings, smartphone policies directly intersect with multiple domains of the health system, including clinical care access, crisis response, public health surveillance, payer alignment, and financial governance. Misalignment between school policy and these domains can generate unintended harm, displacement of risk, or cost transfer across systems.

Clinical & Behavioral Care Interfaces

As schools increasingly play a crucial role in supporting mental health, smartphone restrictions intersect with both prevention and treatment pathways. Restricting daytime (in school) access may reduce exposure to cyberbullying, social comparison, and harmful content – well-established correlates of anxiety, depression, and stress among adolescents.5,35 However, the same devices service as discreet access points to crisis lifelines, suicide prevention text services, and therapist-coordinated digital follow-ups. Removing that channel, without substituting an exception pathway, risks delay in help-seeking, which has been linked to preventable escalations.36,37 Community behavioral health networks and school-linked telemedicine therapy increasingly rely on device-mediated sessions, and bans have already interrupted school-day adherence to digital therapeutic follow-ups.27 Schools may therefore need structured exceptions and referral protocols that preserve access for students with documented behavioral health plans while still reducing population-level exposure to digital triggers.

Surveillance & Public Health Infrastructure

Smartphone bans also influence surveillance capacity for youth mental health and safety. Reduced exposure may help advance prevention targets related to anxiety, sleep disruption, disordered eating, and body image dissatisfaction linked to high-frequency digital engagement.38,39 At the same time, bans can blunt early warning detection if phones are removed before risk signals are visible to reporting systems or staff. Without compensatory infrastructure, schools lose passive digital indicators and must rely on analog observation and self-report. To avoid degradation of surveillance sensitivity, policy implementation should require channels or scheduling controlled windows for digital check-ins to preserve linkage to public health monitoring systems.

Financing, Liability, & Operational Feasibility

Smartphone policy decisions carry financial and legal implications that extend beyond pedagogy. Digital behavioral therapies and app-supported care are increasingly reimbursed by payers;10 policies that disrupt adherence may indirectly increase downstream clinical costs through avoidable deterioration. At the district level, restricting access to smartphones imposes direct expenditures – enforcement hardware such as Yondr pouches cost $12 - $25 per student before replacement, damage, and training costs.11-13 Additional costs accrue from personnel time, compliance monitoring, dispute resolution, and substitute communication systems. Inconsistent enforcement or punitive escalation models can also introduce liability and equity exposure, as seen in Texas where violations carry monetary penalties with disproportionate impact on marginalized students.14 Absent explicit financial and governance planning, the cost of policy implementation can shift from education budgets to health systems in the form of preventable acuity escalation.

Taken together, these system intersections show that school-based smartphone policies function as behavioral-health interventions with system-level consequences – affecting clinical access, surveillance fidelity, care continuity, and cost distribution. The common failure mode across these domains is not the act of restricting devices but restricting them without designed substitutions, exception logic, and governance that can adjust when harm signals emerge. The defining limitation of blanket bans is that they externalize system consequences and rely on discipline to correct design failures. A cyclical, governed policy structure – rather than a terminal rule – allows schools to regulate exposure while continuously realigning with clinical, equity, and operational constraints that evolve over time.

DISCUSSION

Even when structured as HCR models rather than total bans, smartphone restrictions introduce unresolved trade-offs within schools: protecting instructional environments while preserving clinically relevant access, enforcing policy without creating equity distortion, and standardizing guardrails without suppressing local adaptation. These tensions do not disappear under HCR models – they simply shift from “whether to restrict” to “how to restrict without displacing risk to other systems or populations.”

Unintended consequences in HCR models are not hypothetical but observable under real conditions. For example, when a student experiencing panic symptoms is blocked from texting a crisis line during class without an alternative in-school channel, help-seeking is not deferred – it is abandoned. When telemedicine therapy follow-ups scheduled during the school day are interrupted by policy rather than rescheduled through a protected pathway, policy adherence collapses and cases are likely to re-enter crisis care later at a higher acuity. When exceptions are granted informally by “trusted” teachers but denied elsewhere, the rule becomes an equity filter rather than a safety measure, concentrating discipline and appeal burdens on the same student populations most exposed to risk. The proposed framework directly targets these ‘failure points’ by recommending the replacement of discretionary exception-making with pre-authorized channels and by subjecting exception performance – not just rule compliance – to recurring review.

Oklahoma’s “Bell-to-Bell” statute enacted via Senate Bill 139 and signed into law in May 2025, 31 functions as a live implementation laboratory for this logic. While not formally designed as a pilot initiative, the Bell-to-Bell law functions as a real-world test of long-term viability. Although broad in mandate, the law preserves HCR exception pathways for instruction, emergency communication, and documented accommodations while delegating design and enforcement choices to districts.31 This creates real-world variation in how HCR policies perform under different exception architectures, stakeholder engagement levels, and enforcement routines. Additionally, this flexibility creates a decentralized environment where district-level variations enable empirical examination of which designs stabilize and which default to the failure patterns of static bans – offering a rare state-level test bed for HCR policy durability.

CONCLUSION

While smartphones are now embedded into daily life, their unchecked use during school hours is increasingly linked to academic disengagement, heightened social comparisons, and escalating mental health risks among adolescents. In response, many school districts nationwide have introduced restrictive smartphone policies. Yet, most existing policies remain static and singularly focused—centering on discipline, engagement and safety objectives—rather than embracing the holistic approach of integrated public-health interventions. As the evidence reviewed demonstrates, such one-dimensional policies, lacking in exception logic, exception pathways, and iterative oversight, not only fall short in addressing problematic smartphone use (PSU) but risk exacerbating inequities and unintended harms. This policy brief thus advocates for a multidimensional, iterative framework that elevates smartphone design beyond static controls or blanket bans. Central to this four-phase cycle is the meaningful engagement of stakeholders in policy co-design, ensuring that systems’ needs and constraints are accurately identified. Prior to adoption, draft policies should be thoroughly vetted through cognitive, clinical, and equity-based criteria to ensure they are operationally viable and developmentally responsive. Implementation should involve structured rollouts with clear restriction and exception pathways, thereby safeguarding instructional time, supporting effective crisis communication, and accommodating individual learning needs. This framework underscores the necessity of ongoing monitoring and policy refinement, using predefined indicators to evaluate impact and ensure continual alignment with student well-being. By reframing restrictive smartphone policies as adaptive, data-informed, and public health-aligned interventions, this approach not only enhances policy feasibility and legitimacy, but also directly addresses youth mental health concerns in ways that are responsive to developmental needs. Ultimately, the long-term effectiveness and sustainability of smartphone policies will depend less on reaching consensus about the devices themselves, and more on our collective capacity to design, monitor, and revise policies in an adaptive, developmentally grounded, and operationally sound manner. Through this multidimensional and iterative four-phase cycle, school communities can forge durable and relevant policies that truly protect and promote the well-being of all students.

APPENDIX

Appendix 1A: Policy Taxonomy & Definitions

o Total Ban (AKA “Blanket Ban / Prohibition”): Prohibits student smartphone possession/use for the entire school day. Devices are typically surrendered or locked in secured pouches (e.g., Yondr-based district policies in multiple California districts) upon arrival at school and returned only at dismissal from school.

o Hybrid-Conditional Restriction (Instructional-Time Restriction with Structured Exceptions): Restricts use during instructional time while permitting access during designated non-instructional intervals. Preserves pre-authorized substitution pathways for emergency communication, disability-related accommodations, and documented behavioral-health needs (e.g., New York City Department of Education class-period ban).

o Conditional Access Policies (Non-Time-Bound Conditional Models): Permits or restricts access based solely on contextual or individual eligibility criteria (e.g., age level, behavioral history, or documented need), without anchoring restriction to instructional time or schedule.

o Instructional Time: All in-school segments in which students are expected to engage in curricular learning tasks – including lectures, laboratory instruction, group projects that require physical in-school presence for engagement, assessments, and structured classroom discourse.

o Non-instructional Time: Scheduled school periods not designated for curricular learning (e.g., lunch, passing periods, recess, advisory periods, and arrival/dismissal windows)

Appendix 1B: Key Stakeholders

• Students: Are the primary focus of school-wide smartphone policies, with their perspectives varying by age, development, cultural background, and digital dependence.

• Parents & Guardians: Views on smartphone restrictions are shaped by their roles as caregivers and advocates for their children’s safety, academic aspirations, emotional health, and socioeconomic context.

• Educators: Prioritize pedagogy, student well-being, and classroom management.

• Policymakers: Must reconcile public health priorities with legal protections and local conditions amid electoral pressures.

• Legal/Advocacy Organizations: Shape the policy discourse around civil liberties, educational equity, and youth mental health.

Appendix 1C: Tracked Indicators

1. Equity distribution of disciplinary action to detect disparate impact

2. Adherence and compliance burden for instructional staff

3. Frequency and resolution of crisis-access or accommodation exceptions

4. Mental-health-relevant flags such as blocked access to protective supports or increases in behavioral referrals

5. Volume and content of formal appeals or grievances

6. Unintended effects such as policy-driven conflict, covert use, or displacement to other platforms

REFERENCES

1. Verlenden JV, Fodeman A, Wilkins N, et al. Mental health and suicide risk among high school students and protective factors — youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2023. MMWR Supplements. 2024;73(4):79-86. doi:10.15585/mmwr.su7304a9

2. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior survey data summary & trends report: 2013–2023. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/yrbs/dstr/pdf/YRBS-2023-Data-Summary-Trend-Report.pdf

3. Burnell K, Maheux AJ, Shapiro H, Flannery JE, Telzer EH, Kollins SH. Smartphone engagement during school hours among US youths. JAMA Network Open. 2025;8(8):e2523991. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.23991

4. Abi-Jaoude E, Naylor KT, Pignatiello A. Smartphones, social media use and youth mental health. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2020;192(6):E136-E141. doi:10.1503/cmaj.190434

5. Twenge JM, Joiner TE, Rogers ML, and Martin GN. Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among U.S. adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clinical Psychological Science. 2017;6(1):3-17. doi:10.1177/2167702617723376

6. Carter B, Ahmed N, Cassidy O, et al. ‘There’s more to life than staring at a small screen’: a mixed methods cohort study of problematic smartphone use and the relationship to anxiety, depression and sleep in students aged 13–16 years old in the UK. BMJ Mental Health. 2024;27(1):e301115. doi:10.1136/bmjment-2024-301115

7. Radesky JS, Weeks HM, Schaller A, et al. Constant companion: a week in the life of a young person’s smartphone use. Common Sense; 2023. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/research/report/2023-cs-smartphone-research-report_final-for-web.pdf

8. Riehm KE, Feder KA, Tormohlen KN, et al. Associations between time spent using social media and internalizing and externalizing problems among US youth. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(12):1266. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2325

9. Do KT, Grammer JK, Bishop JP. Strengthening K-12 cellphone policies to support student learning and well-being. UCLA and UC|CSU Collaborative for Neuroscience, Diversity, and Learning; 2025. https://transformschools.ucla.edu/research/strengthening-k-12-cellphone-policies-to-support-student-learning-and-well-being-research-based-guidance-for-u-s-education-leaders/

10. Litke SG, Resnikoff A, Anil A, et al. Mobile technologies for supporting mental health in youths: scoping review of effectiveness, limitations, and inclusivity. JMIR Mental Health. 2023;10:e46949. doi:10.2196/46949

11. Kadvany E. The cost of cellphones: teachers, students, parents debate banning phones from classrooms. Palo Alto Online. Published 2019.

https://www.paloaltoonline.com/news/2019/09/27/the-cost-of-cellphones-teachers-students-parents-debate-banning-phones-from-classrooms/#:~:text=The%20pouches%20cost%20about%20$12,them%20use%20a%20landline%20phone.

12. Jacobson L. So your school wants to ban cellphones. Now what? Route Fifty. Published 2024. https://www.route-fifty.com/digital-government/2024/08/so-your-school-wants-ban-cellphones-now-what/398659/#:~:text=%27Loopholes%27,business%20from%202022%2C%20GovSpend%20shows.

13. Jones C, Johnson K. More California schools are banning smartphones, but kids keep bringing them. CalMatters. https://calmatters.org/economy/technology/2024/08/phone-bans-newsom-lessons/. Published August 21, 2024.

14. Sequeira R. School cellphone bans spread across states, though enforcement could be tricky. Stateline. Published 2025. https://stateline.org/2025/02/24/school-cellphone-bans-spread-across-states-though-enforcement-could-be-tricky/#:~:text=U.S.%20Education%20Department%20pings%20states,for%20violating%20a%20cellphone%20ban.

15. Regional Educational Laboratory Northeast & Islands. Multi-Tiered Systems of Support and the Importance of Promoting Student Well-being. Institute of Education Sciences; 2024. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/rel/regions/northeast/pdf/MTSS_Importance_of_Promoting_Student_Well-being_Fact_Sheet.pdf

16. Bozzato P, Longobardi C. School climate and connectedness predict problematic smartphone and social media use in Italian adolescents. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology. 2024;12(2):83-95. doi:10.1080/21683603.2024.2328833

17. Marshall D. When School Policy Limits Access to Assistive Technology for Students with Disabilities. Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates (COPAA). Published September 10, 2024. https://www.copaa.org/news/681778/When-School-Policy-Limits-Access-to-Assistive-Technology-for-Students-with-Disabilities.htm

18. Arundel K. Parents push back on school cellphone bans. K-12 Dive. https://www.k12dive.com/news/safety-concerns-school-cell-phone-bans-mental-health/726668/. Published September 12, 2024.

19. Hugh-Jones S, Pert K, Kendal S, et al. Adolescents accept digital mental health support in schools: A co-design and feasibility study of a school-based app for UK adolescents. Mental Health & Prevention. 2022;27:200241. doi:10.1016/j.mhp.2022.200241

20. Gath ME, Monk L, Scott A, and Gillon GT. Smartphones at school: a mixed-methods analysis of educators’ and students’ perspectives on mobile phone use at school. Education Sciences. 2024;14(4):351. doi:10.3390/educsci14040351

21. Anderson M, Gottfried J, and Park E. Most Americans back cellphone bans during class, but fewer support all-day restrictions. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/10/14/most-americans-back-cellphone-bans-during-class-but-fewer-support-all-day-restrictions/. Published October 14, 2024.

22. Smale WT, Hutcheson R, and Russo CJ. Cell phones, student rights, and school safety: finding the right balance. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy. 2021;(195):49-64. doi:10.7202/1075672ar

23. NC Education Lawyer. (2025, March 25). Considerations and Legal Implications of Banning Cell Phones in School. Neubia Harris. https://www.neubiaharrislaw.com/post/considerations-and-legal-implications-of-banning-cell-phones-in-school#:~:text=However%2C%20the%20decision%20to%20ban,schools%20to%20regulate%20student%20behavior.

24. Walker T. Take cellphones out of the classroom, educators say. NeaToday. https://www.nea.org/nea-today/all-news-articles/take-cellphones-out-classroom-educators-say. Published 2024.

25. Thompson W. Be “Yondr” the schoolhouse gate: law and policy for student cell phone restriction in public high schools. Suffolk Journal of Trial and Appellate Advocacy. 2024;29(1). https://dc.suffolk.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1599&context=jtaa-suffolk

26. Battaglia J, Battaglia G. New York teachers union calls for ‘bell-to-bell’ cell phone restrictions in schools. Rochester First. Published 2024. https://www.rochesterfirst.com/news/top-stories/new-york-teachers-union-calls-for-bell-to-bell-cell-phone-restrictions-in-schools/

27. Soon K, Suter JC, Linkous O, Davis CA, and Bruns EJ. Adapting community-based wraparound for use as an intensive intervention in schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. Published online 2025. doi:10.1177/10983007251335916

28. Langreo L. Cellphone bans can ease students’ stress and anxiety, educators say. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/cellphone-bans-can-ease-students-stress-and-anxiety-educators-say/2023/10. Published October 16, 2023.

29. New York State. Distraction-Free Schools: Governor Hochul Announces New York to Become Largest State in the Nation with Statewide, Bell-to-Bell Restrictions on Smartphones in Schools. Governor Kathy Hochul. Published 2025. https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/distraction-free-schools-governor-hochul-announces-new-york-become-largest-state-nation

30. Figlio D, Özek U. The Impact of Cellphone Bans in Schools on Student Outcomes: Evidence From Florida. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2025. doi:10.3386/w34388

31. Martinez-Keel N. Oklahoma governor signs mandatory one-year school cellphone ban into law. KOSU. https://www.kosu.org/education/2025-05-06/oklahoma-governor-signs-mandatory-one-year-school-cellphone-ban-into-law. Published May 6, 2025.

32. Georgia Department of Education (GaDOE). Guidance to Support the Distraction-Free Education Act. Georgia Department of Education; 2025. https://login.community.gadoe.org/documents/guidance-to-support-the-distraction-free-education-act-august-2025

33. Goodyear VA, Randhawa A, Adab P, et al. School phone policies and their association with mental well-being, phone use, and social media use (SMART Schools): a cross-sectional observational study. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe. 2025;51. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2025.101211

34. Scott M, Schildkraut J. School cell phone bans & restrictions. Rockefeller Institute of Government. Published 2025. https://rockinst.org/blog/school-cell-phone-bans-restrictions/#:~:text=In%20line%20with%20such%20efforts,Education%20Services%20(BOCES)%20comply.

35. Shannon H, Bush K, Villeneuve PJ, Hellemans KG, Guimond S. Problematic social media use in adolescents and young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mental Health. 2022;9(4):e33450. doi:10.2196/33450

36. Gould MS, Munfakh JLH, Lubell K, Kleinman M, and Parker S. Seeking help from the internet during adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(10):1182-1189. doi:10.1097/00004583-200210000-00007

37. Memon A, Sharma S, Mohite S, and Jain S. The role of online social networking on deliberate self-harm and suicidality in adolescents: a systematized review of literature. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2018;60(4):384. doi:10.4103/psychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_414_17

38. Burnell K, Andrade FC, and Hoyle RH. Longitudinal and daily associations between adolescent self-control and digital technology use. Developmental Psychology. 2022;59(4):720-732. doi:10.1037/dev0001444

39. Nagata JM, Cortez CA, Cattle CJ, et al. Screen time use among US adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatrics. 2021;176(1):94. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.4334

40. Schneider SK. A Multi-Tiered approach to digital wellness. Edutopia. Published December 3, 2024. https://www.edutopia.org/article/promoting-safe-digital-media-use/