Program Director Knowledge of GME across an Osteopathic Medical Education Consortium

Jeffrey S. Stroup, PharmD, James D. Hess, Ed.D.

Oklahoma State University - Center for Health Sciences

Abstract

Context: Graduate medical education (GME) programs in the United States (US) are responsible for developing the future physician workforce. While GME funding remains a critical aspect of physician training, it is being considered as an area that can be potentially targeted for cuts by the federal government to solve budgetary issues. To better understand physician knowledge of GME funding overall in our region, we surveyed GME program directors of an osteopathic GME consortium to assess their knowledge level of GME funding.

Methods: The sample size for this study consisted of 25 program directors of either residency or fellowship programs in the Osteopathic Medical Education Consortium of Oklahoma (OMECO). Assessment of the program directors was through a survey-based tracking tool.

Results: A total of 12 responses were received for the survey. The most notable and significant finding of the survey was the general lack of knowledge regarding GME programs. With respect to DGME (direct graduate medical education) funding, 83% of respondents were unaware of the amount of funding the program received for resident stipends. Additionally, none of the respondents were aware how much funding was received for faculty programming.

Conclusions: GME funding is critical to the advancement of medicine in the US. The knowledge of GME funding must be enhanced at the program director level to ensure that those ground leaders of GME can take the funding message to a higher level.

Introduction

Graduate medical education (GME) programs in the United States (US) are responsible for developing the future physician workforce which includes a strong primary care training arena. The goal of Affordable Care Act (ACA) was to improve access to healthcare and embrace population health through the primary care workforce. Public support for GME programs is estimated to be over $13 billion per year, funded primarily by Medicare through two payment mechanisms. 1 Direct graduate medical education (DGME) funds pay for resident salaries and faculty supervisor compensation.1,2 Indirect graduate medical education (IME) funds are allocated to compensate teaching hospitals for the increased costs associated with hosting these training programs. IME funds were initiated by Medicare due to the following assumptions: 1) patients tend to be sicker, 2) staff productivity can be lower, and 3) costs can be greater due to higher diagnostic utilization associated with training programs. 1,2 IME funds are supplemented to the inpatient Medicare payment rate for institutions with GME programs. Thus, IME payments are tied to inpatient volume, case mix, and residency size based on the IME cap set by Medicare.

GME program funding was introduced in 1965 with the establishment of Medicare. 3 At that time, hospitals were able to add GME costs to their medical bills as usual and customary charges. In 1997, the Balanced Budget Act capped the number of training programs that Medicare would fund primarily due to concerns of increased costs in physician training. 3 DGME payments are based on a hospital-specific per resident payment amount that was determined in 1984 and is updated for inflation. Since 1997, IME payment adjustments have decreased, and in 2010 the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) recommended that a portion of IME payments be made contingent upon reaching desired educational outcomes and objectives. 2 Despite the cap put in place in 1997, over 15,000 new residency slots have been added that are “over cap.” 3,4 These residency programs are not funded through Medicare and in fact are

In addition to Medicare, state Medicaid programs have paid over $3.78 billion to support GME programs. 5 Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals have also contributed to GME funding as over one third of all residents rotate through VA facilities during their training. 6 Several states also support GME through different legislative initiatives. In Oklahoma, the legislature has appropriated funds in years past to support rural residency program development across the state. 7

While GME funding remains a critical aspect of physician training, it is being considered as an area that can be potentially targeted for cuts by the federal government to solve budgetary issues. 1,2 In order to successfully advocate for continued federal support, it is important that each GME program and program director understand the components and funding mechanisms of the GME programs.

In 2008, the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine (APDIM) performed a survey to assess program director knowledge of GME funding.8 As a follow-up to that study and to better understand GME funding overall in our region, we surveyed GME program directors of an osteopathic GME consortium to assess their knowledge level of GME funding.

Methods

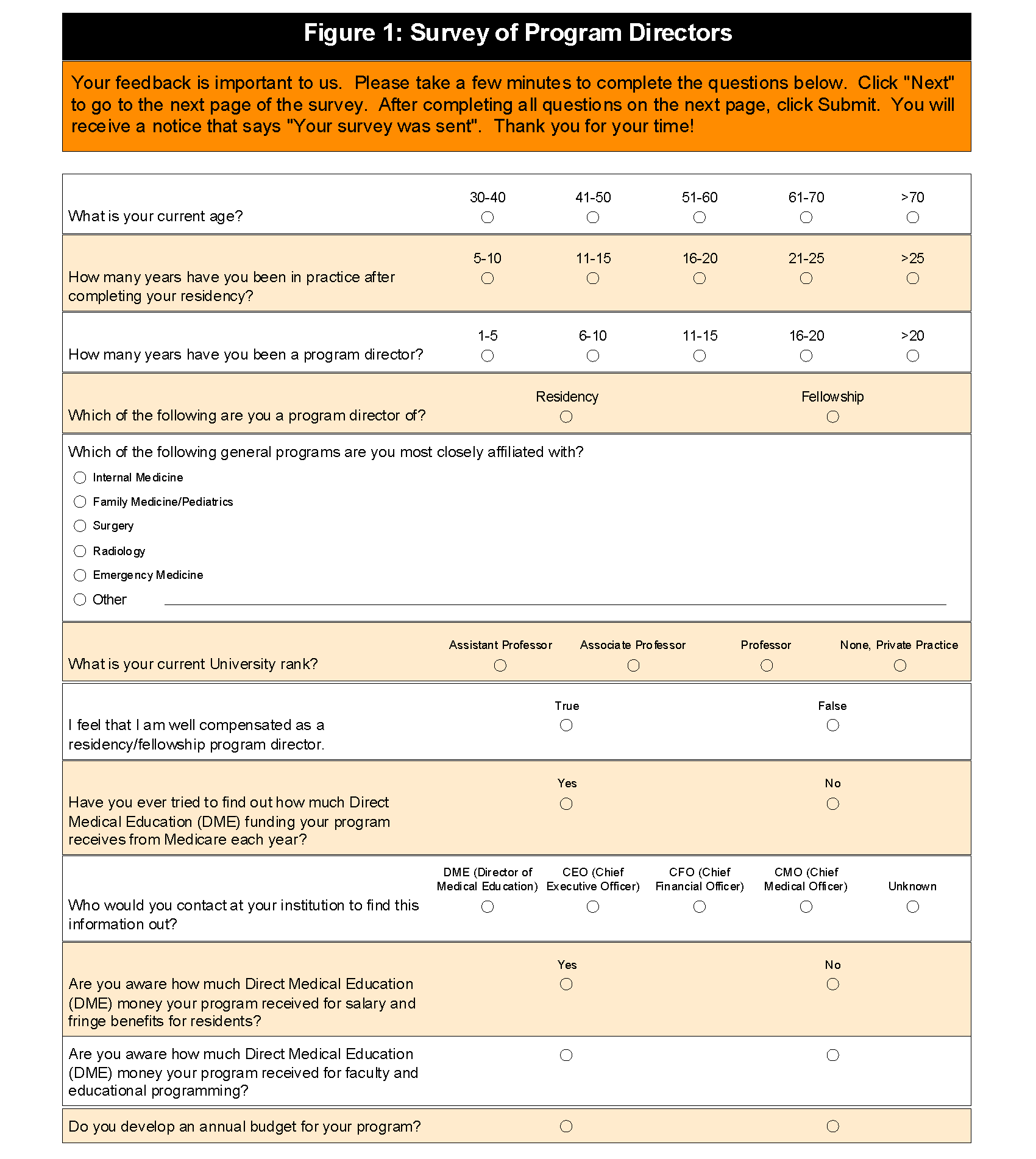

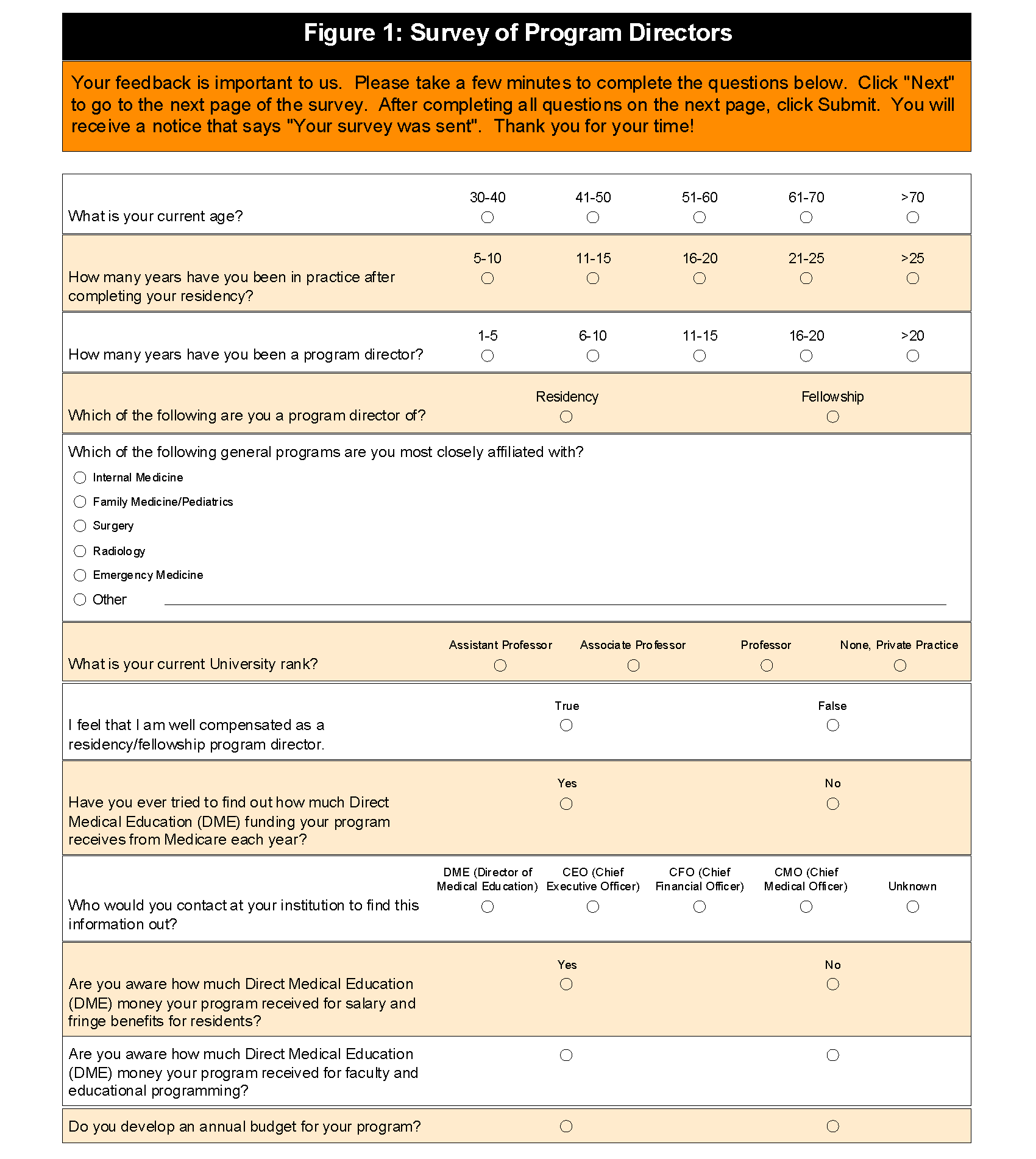

The primary purpose of this study was to assess by survey the knowledge of residency program directors as it relates to GME funding. The sample size for this study consisted of 25 program directors of either residency or fellowship programs in the Osteopathic Medical Education Consortium of Oklahoma (OMECO). The questions for the program director survey (figure 1) were uploaded by the Oklahoma State University (OSU) Center for Health Sciences Office of Educational Development (OED) and entered into the SurveyTracker program.

The OED designee emailed the survey to the identified OMECO program directors for completion. After approval by the OSU Institutional Review Board (IRB), the survey was launched on October 1, 2013 and concluded on December 1, 2013. Reminders were emailed to all program directors every two weeks to complete the survey. All reminder emails were approved by the OSU IRB.

Participation in the study was voluntary, and the survey program utilized was set-up in an anonymous mode. Therefore, all responses to this survey were confidential. All survey results were reviewed by the authors and all study data was kept confidential.

Results

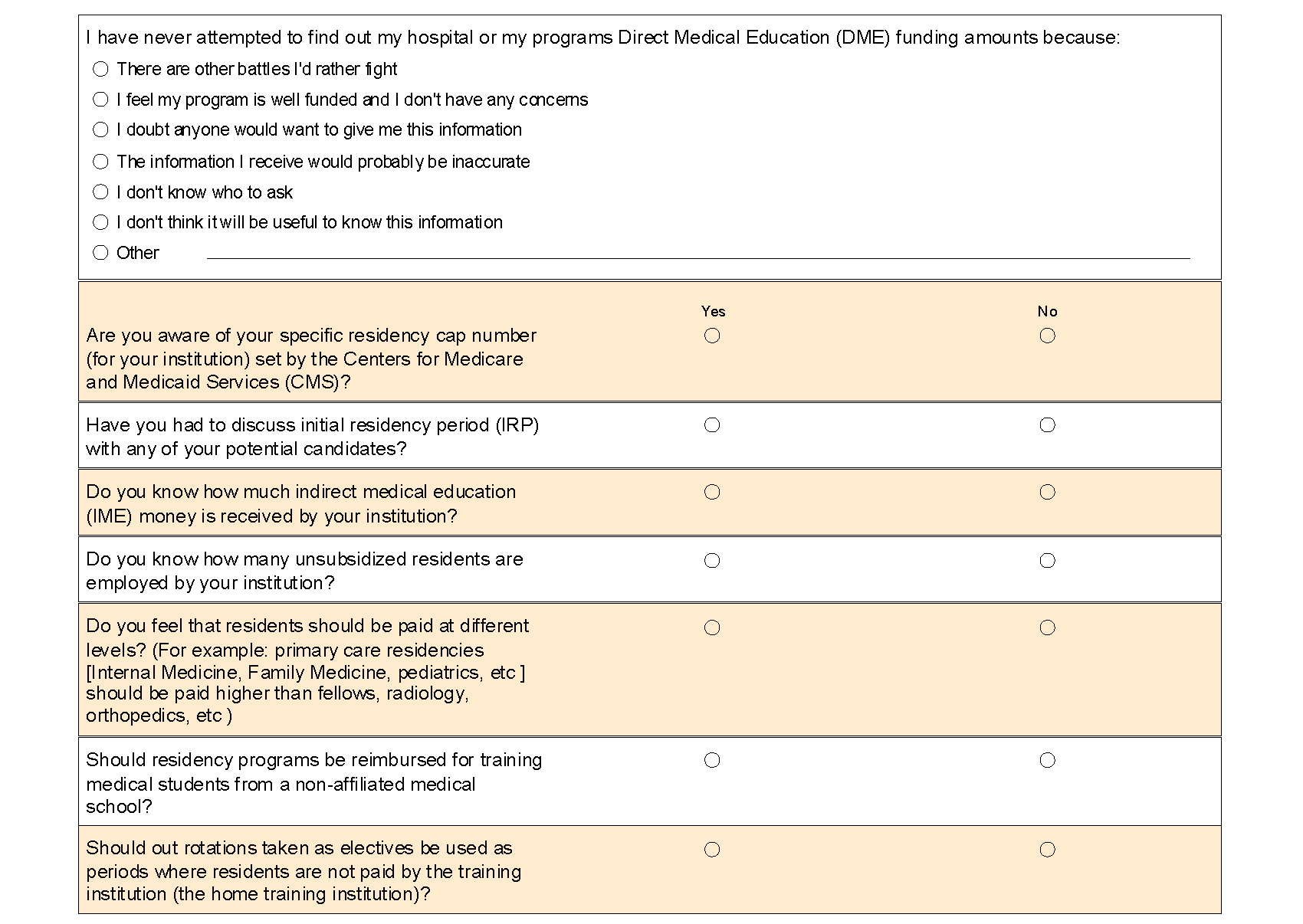

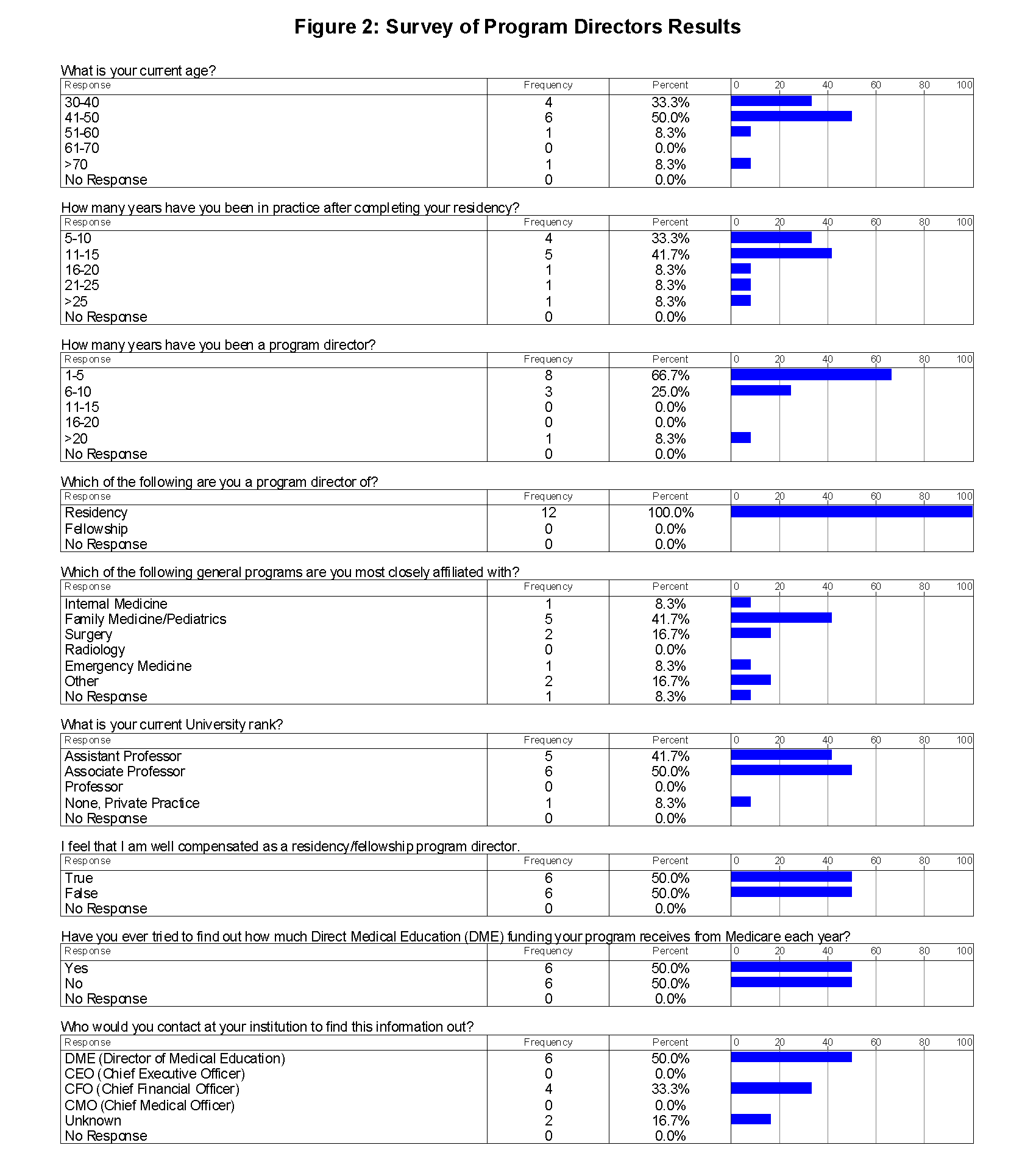

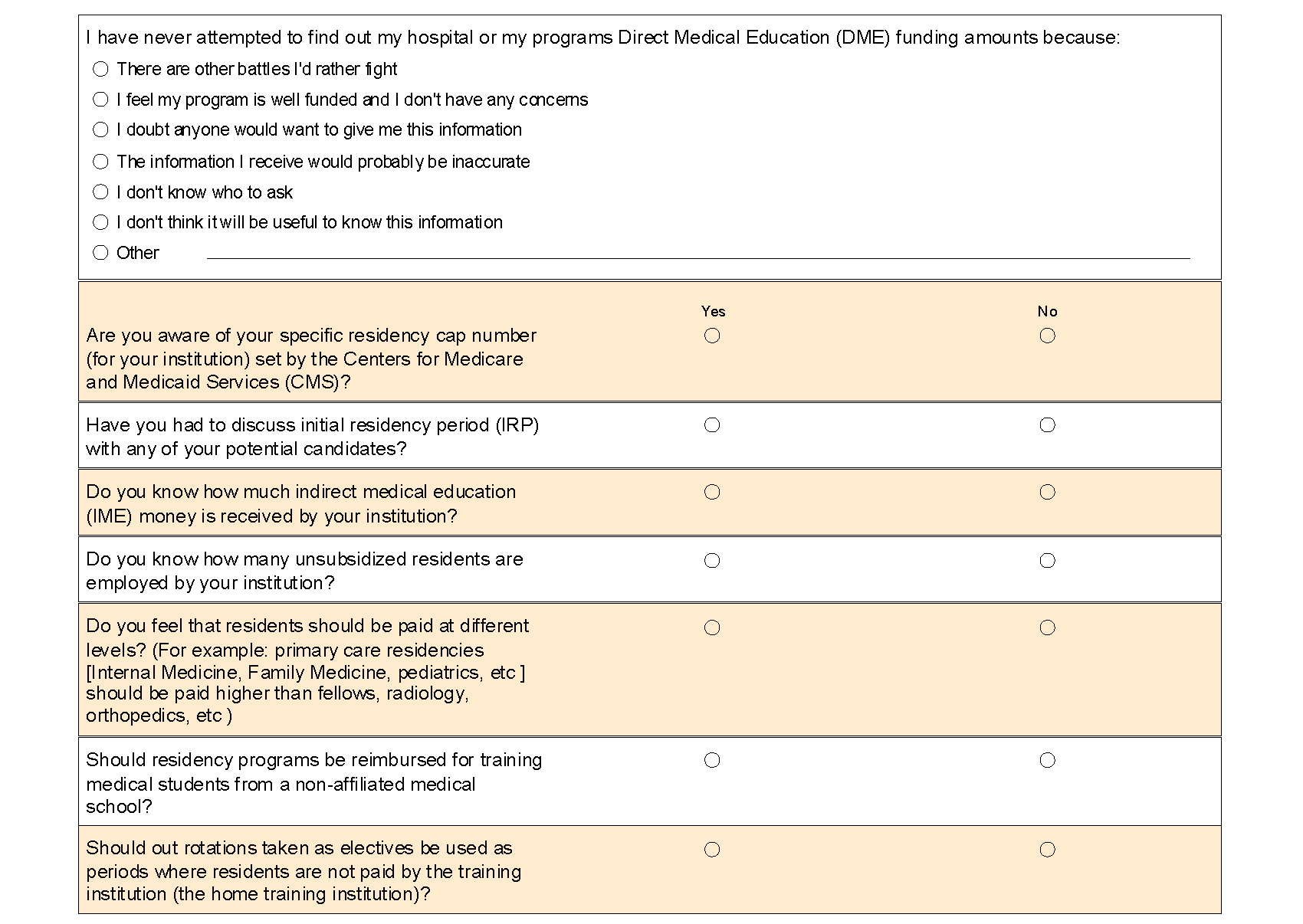

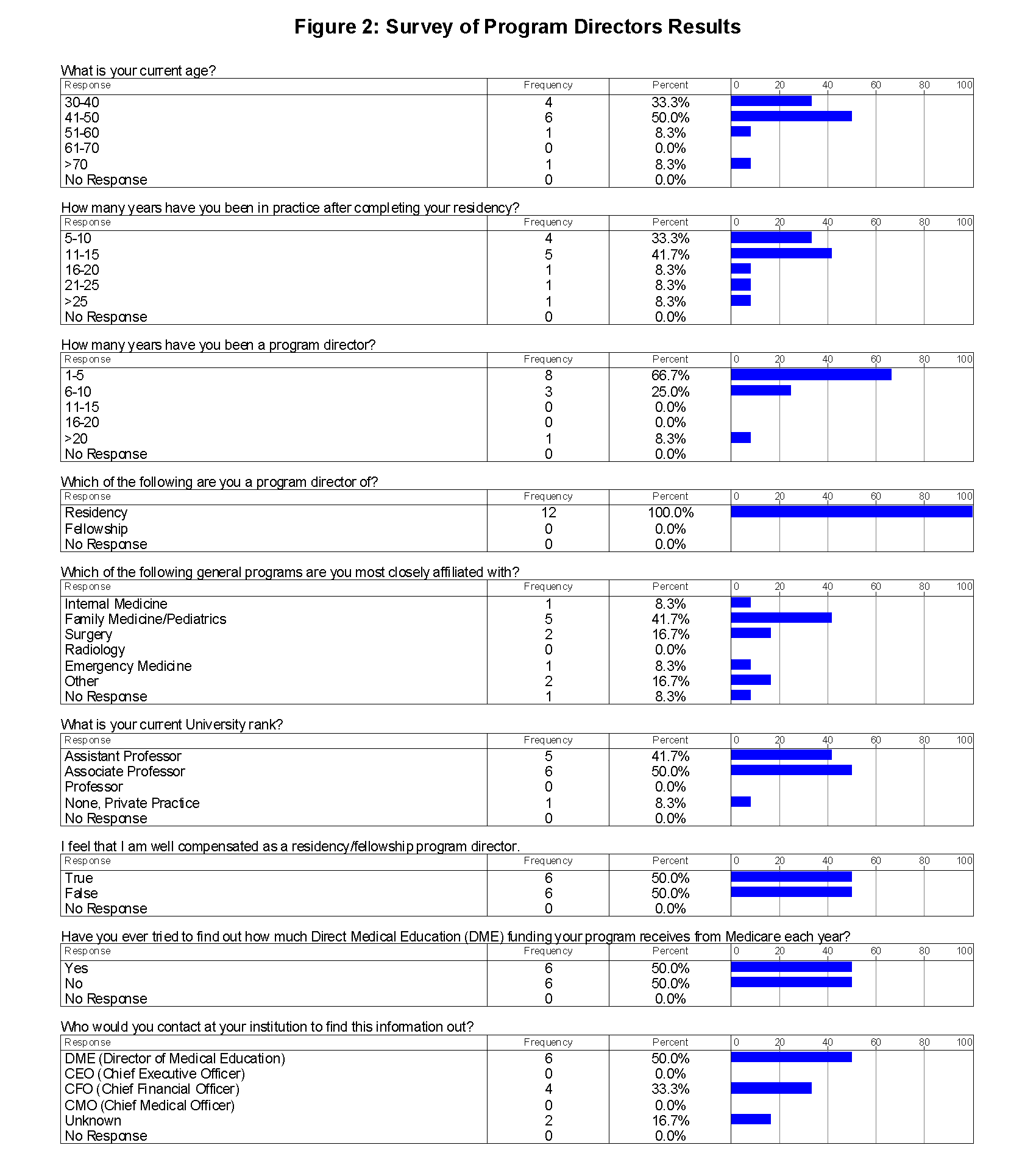

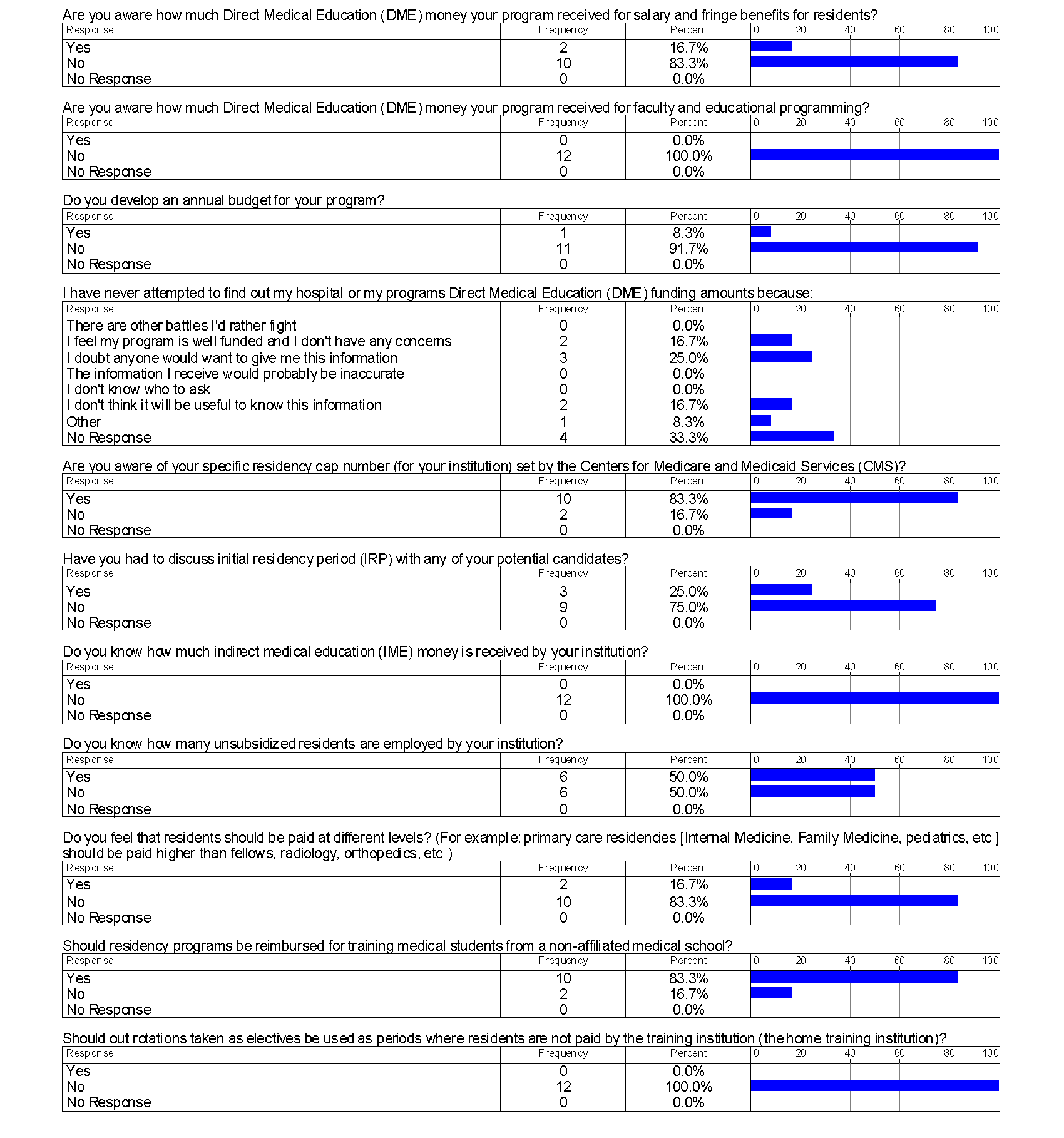

A total of 12 responses were received for the survey (figure 2).

All of the responses were from program directors of residency programs. In general, the majority of respondents (83%) were less than 50 years old, had been in practice less than 20 years (83%), had been a program director for less than 10 years (93%), and were faculty members (93%).

The most notable and significant finding of the survey was the general lack of knowledge regarding GME programs. With respect to DGME funding, 83% of respondents were unaware of the amount of funding the program received for resident stipends. Additionally, none of the respondents were aware how much funding was received for faculty programming. Despite this acknowledged gap in awareness, only 50% of respondents ever attempted to find out through any source how much DGME funding was received. Moreover, none of the respondents were aware of the amount of IME funds received. Despite being aware of the residency caps set by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and unsubsidized residents employed at the institution, general funding knowledge of GME programs appeared to be lacking.

Discussion

GME funding is both a necessary and costly program to the US. In the current climate of the ACA and targeted healthcare reform, finances in the healthcare sector are being squeezed from all directions in an effort to lower the costs of care yet provide enhanced outcomes. While GME funding has been targeted under several proposed expenditure reduction plans, pressures to increase the number of graduating physicians persist.9-11 Further exacerbating this problem is the Supreme Court’s position that states may opt out of Medicaid expansion. 12. This ruling has further put safety net hospitals (hospitals or health systems that care for a high level of low-income, un-insured, and vulnerable populations) and training institutions in a financial position where GME expansion has been placed on hold due to the financial uncertainties of the impact of the ACA. Not coincidently, several institutions have decided to cut the GME slots not supported by federal funding because those hospitals simply cannot bear the cost of maintaining the training programs without some form of reimbursement. In light of these changes in the healthcare finance landscape, it is imperative that residency program directors become engaged in understanding GME funding and developing alternative funding ideas to support their programs. In our survey, the lack of overall GME funding knowledge was eye opening. If program directors do not understand funding mechanisms for GME, how can they advocate for the expansion of programs or changes in programs?

Understandably, MedPAC has recommended that greater transparency exist in GME funding and has recommended that residency programs be held financially accountable for the training that results from public funding. 2 To date, it remains unclear how this will be accomplished. A recommendation has been made that some GME funds be withheld and paid in a supplementary manner based on quality. This approach has already been applied to health systems under the value based purchasing approach as it relates to outcomes in the hospital with Medicare beneficiaries. 13. Public reporting has become very popular in medicine in recent years with the implementation of Open Records and Sunshine Acts and the newly discussed Medicare physician payment reporting. 14,15 Another logical step toward transparency may be to publically publish the amount of funding provided to hospitals that train residents as well as to identify where the graduated residents practice. For instance, if urban programs only produce urban doctors the programs are not supporting the entire landscape of physician need in the state and country.

Continued GME support and funding is imperative to maintain the physician pipeline necessary to affect health outcomes in the US. Today, at an alarming rate, medical schools are graduating more medical students than residency slots exist to support those graduates. 16 This condition is intolerable in that medical students are incurring a tremendous debt, but may not be able to utilize their degree. Couple this with the annual influx of 6,000 foreign medical graduates into the GME system and a perfect storm exists. 17 In addition to the lack of GME slots available, with the passage of the ACA, several older physicians are deciding to retire early rather than adjust to the practice changes brought on by the reforms. This culmination of problems will ultimately affect the patients that everyone is attempting to help. At the heart of the issue with GME funding nationwide is the imbalance of funding among the states. For instance, New York has more Medicare funded residents than 31 other states combined. 18 In addition, the payment formulas for residents reflect huge variations across states. States in the Northeast of the United States have higher residency caps per 100,000 population and receive higher GME payments.18 In fact, Medicare GME funding contributes $103.63 per person in New York as compared to $1.94 per person in Montana. 18 New York receives a total of greater than $2 billion in GME payments annually as compared to $1.9 million in Montana annually. 18 This historical disparity in funding among states should be unacceptable, and because physicians typically practice in geographic areas where they train, the problem becomes self-perpetuating. Therefore, a review of GME funding nationwide should be sought to equate these imbalances.

Despite multiple studies on the reality of physician shortages and the subsequent impact on health outcomes, the appetite for change and reform in Washington, DC is lacking. Multiple house and senate bills over the past 10-15 years to address GME financing have died either in committee or on the floor. 19,20 Given this political reality, local and state mechanisms by which GME can be supported should be sought. The first step in moving GME funding forward on a local and state level is to ensure that the physicians providing the GME training understand the current funding mechanisms. The next step would be to develop a working group to foster new funding ideas. Such groups must be comprised of physician trainers, hospital and university leaders, financial specialists, and legislative leaders.

In our survey we posed questions around changes in resident pay and rotations taken as electives. For example, should residency institutions that have specialty programs pay those specialty residents and fellows at a lower rate than the primary care training program residents? In addition, if electives (non required rotations) are taken outside of the healthcare system should residents not be paid for that month of experience by the home training hospital? Generally speaking, program directors were not open to these unique changes in residency programs to utilize financial resources. Perhaps their aversion to it was because it was asked of them and not brainstormed our developed through a working group. These ideas need to be brought to the table in future negotiations to develop the best path forward to keep GME sustainable at a local and even national level. Another solution may be to identify medical students early on who want to pursue a primary care track. If identified, perhaps their fourth year of medical school could in fact be turned into an internship year of residency. 21 This would certainly require a change in medical school training. Other ideas on a national level are to engage with Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) to cost share programs. 22 Some states are partnering with private insurance carriers to develop GME funding by allowing residency training costs to be accounted for in calculation of medical loss ratios. 23 Others are utilizing the expansion of Medicaid under the ACA to develop GME funding models. 24

While reform of GME at the national level has not experienced much success, discussion of reductions in GME funding proliferate. Committees such as the Simpson-Bowles Commission, MedPAC, and even proposals from President Obama have all discussed cutting GME. 9-11 From the perspective of the physician trainer this seems ridiculous; but such discussions must be taken seriously. To truly understand the GME funding issue, one must also focus on the future physician workforce. Medical students and residents often move towards subspecialties to garner increased compensation. In reality, the future of medicine with the passage of the ACA should focus on the primary care workforce and supporting that endeavor. 21 GME programs and state legislators should look at the funding mechanisms to support right-sizing residency programs to focus on primary care physicians to practice in rural and underserved urban areas. By right-sizing these programs, institution costs may decrease by limiting the number of high cost subspecialty training programs. The salient point here is that for true reform of GME funding to occur, all aspects of the GME program must be reviewed and analyzed as a whole, not in piece meal fashion.

Conclusion

Despite our best efforts to encourage program directors to complete the survey, only twelve responses were received out of the potential twenty five. These respondents did, however, give us a glimpse into the general thought patterns of the program directors. Our hope would be that on a national level, the osteopathic training leaders would develop a national survey to attain the thoughts of all program directors of osteopathic training programs. With that information in hand, a national working group could be convened to develop a pathway that could be applied to training institutions at the local level. On a final and ironic note, it is worth stating that prior to the survey the program directors attended a mandatory one-hour GME review session. In this session, a national osteopathic GME expert reviewed GME funding and its relevant mechanisms with all of the program directors. Despite this recent training session, it appears that the program directors still lacked the knowledge necessary to fully understand as well advocate for the GME funding issue. Perhaps program directors view the financing aspects of GME as uninteresting or “someone else’s job.” Or perhaps no one really cares about GME funding until a crisis is in full swing. From this we can only conclude that the road to GME financial literacy is a long and arduous one.

GME funding is critical to the advancement of medicine in the US. The knowledge of GME funding must be enhanced at the program director level to ensure that those ground leaders of GME can take the funding message to a higher level within their organizations and to state leaders to advocate for their training programs. A national review and reform of GME must be undertaken to ensure the program remains intact. While a national reform is needed, state and local leaders must convene to develop unique ideas to support GME funding.

References

1. Council of Graduate Medical Education. Twenty-first report: improving value in graduate medical education [Internet]. Rockville (MD): COGME; 2013 Aug [cited 2014 Feb 20]. Available from: http://www.hrsa.gov/advisorycommittees/bhpradvisory/cogme/Reports/ twentyfirstreport.pdf

2. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. 2010. Report to Congress: Aligning Incentives in Medicare. Washington, DC: MedPAC.

3. Iglehart JK. Financing Graduate Medical Education - Mounting Pressure for Reform. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366: 1562-1563.

4. Brotherton SE, et al. Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate medical education, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2012; 308: 2264–79.

5. Chen C, Petterson S, Phillips RL, Mullan F, Bazemore A, O’Donnell SD. Toward graduate medical education (GME) accountability: measuring the outcomes of GME institutions. Acad Med. 2013; 88: 1267-1280.

6. Goodman DC, Robertson RG. Accelerating physician workforce transformation through competitive graduate medical education funding. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013; 32: 1887-92.

7. Oklahoma Hospital Residency Training Program Act, HB 3058, Oklahoma Legislature (2012).

8. Chaudhry SI, Khanijo S, Halvorsen AJ, McDonald FS, Patel K. Accountability and transparency in graduate medical education expenditures. Am J Med. 2012; 125: 517-522

9. Salsberg E, Rockey PH, Rivers KL, Brotherton SE, Jackson GR. US residency training before and after the 1997 Balanced Budget Act. JAMA. 2008; 300: 1174–80.

10. National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform. The moment of truth: report of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform [Internet]. Washington (DC): White House; 2010 Dec [cited 2014 Feb 20]. Available from: http://www.fiscalcommission.gov/sites/fiscalcommission.gov/files/documents/TheMomentofTruth12_1_2010.pdf

11. Office of Management and Budget. Budget of the United States government, fiscal year 2014 [Internet]. Washington (DC): OMB; 2013 [cited 2014 Feb 20]. Available for download from: http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Overview

12. Graves JA. Medicaid expansion opt-outs and uncompensated care. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367: 2365-2367.

13. Chatterjee P, Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Patient experience in safety net hospitals. Arch Intern Med. 2012; 172: 1204-1210.

14. Agrawal S, Brennan N, Budetti P. The sunshine act-effects on physicians. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368: 2054-2057.

15. Department of Health and Human Services. Modified policy on freedom of information act disclosure of amounts paid to individual physicians under the Medicare program. Fed Regist. 2014; 79: 3205-3206.

16. Iglehart JK. The residency mismatch. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 297-299.

17. Gomez PP, Willis RE, Jaramillo LA. Evaluation of a dedicated, surgery-oriented visiting international medical student program. J Surg Educ. 2013 [article in press].

18. Mullan F, Chen C, Steinmetz E. The geography of graduate medical education: imbalances signal need for new distribution policies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013; 32: 1914-1921.

19. All-Payer Graduate Medical Education Act of 2001. H.R. 2178, 107th Cong. (2001).

20. Medical Education Trust Fund Act of 2001. S. 743, 107th Cong., (2001).

21. Shannon SC, Buser BR, Hahn MB, Crosby JB, Cymet T, Mintz JS, Nichols KJ. A new pathway for medical education. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013; 32: 1899-1905.

22. Florida Medicaid, SB 1646, Florida Legislature (2012).

23. Florida Medicaid Managed Care, SB 730, Florida Legislature (2012).

24. Spero JC, Fraher EP, Ricketts TC, Rockey PH. GME in the United States: a review of state initiatives. Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. September 2013.